[Part 1 of this article (“Chicago Society’s 1894 Charity Bazaar”) describes the planning and organization of a novel society fundraiser called “Echoes of the White City” held in Chicago during the fall of 1894.]

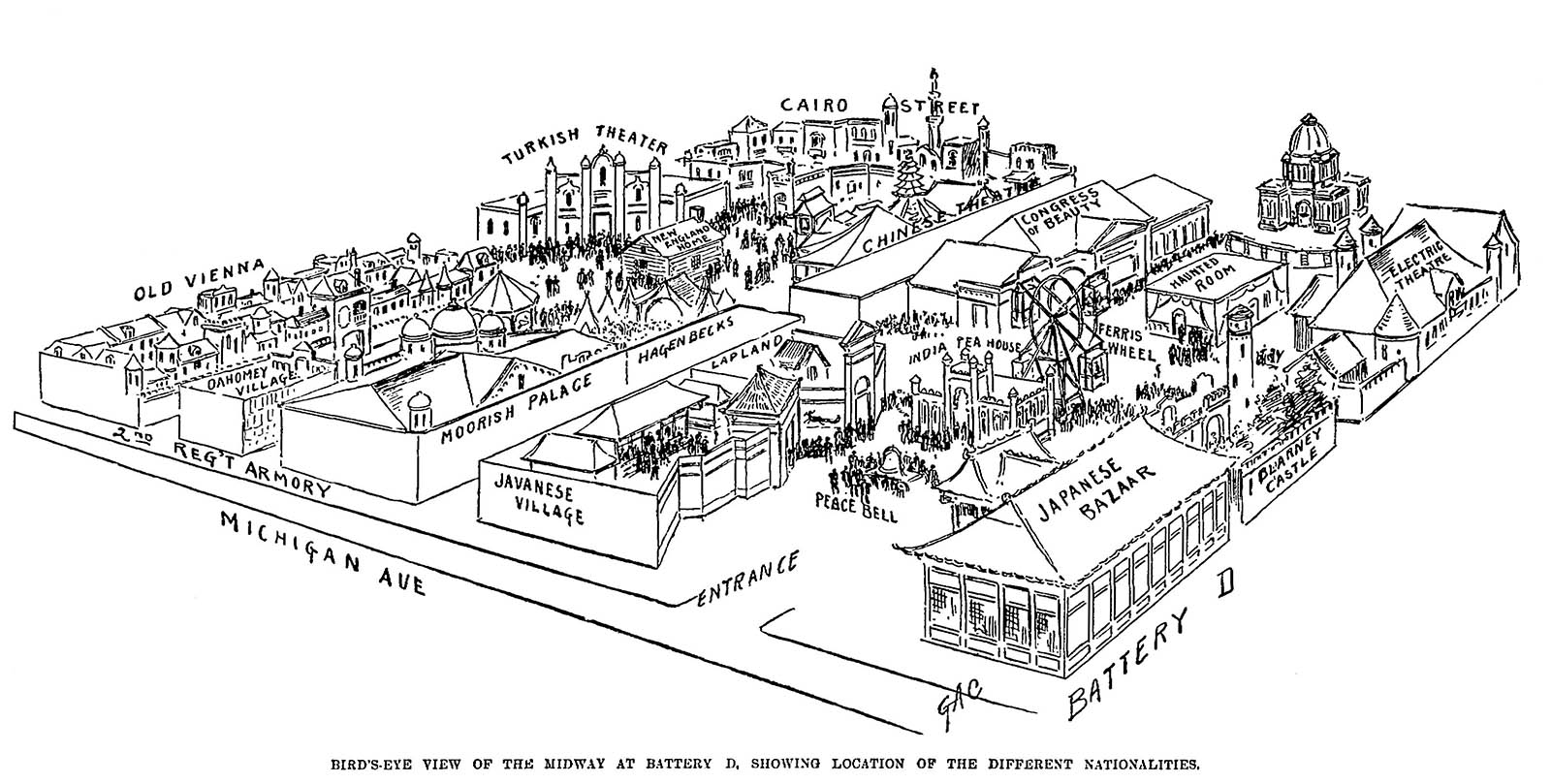

For two weeks in November of 1894, an ersatz Midway Plaisance sprang to life inside of the Battery D Armory and Second Regiment Armory buildings in downtown Chicago. “Echoes of the White City—The Midway” offered patrons a chance once again to walk down the great entertainment street of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Populating the miniature villages and booths representing “every land on the globe from Iceland to Patagonia” [“Reviving the Midway”] were hundreds among Chicago’s social elite. They came together to raise money for two worthy children’s charities … and to have some fun.

Wont to amaze and amuse

As guests arrived on the evening of Tuesday, November 13, they encountered a revival of the marvelous Midway Plaisance of the 1893 World’s Fair. Fakirs “wont to amaze and amuse all comers with their droll and comical conceits” enticed visitors into many of the nearly twenty reproductions of international villages and other attractions. [“College Boys’ Yells”]

A birds-eye-view of the attractions of “Echoes of the White City” inside of the Battery D Armory (right side) and the Second Regiment Armory (left side) in downtown Chicago in November of 1894. [Image from the Chicago Daily Tribune, Nov. 13, 1894.]

Old Vienna

One of the more popular international villages of the original Midway was the Austrian Village. Commonly called “Old Vienna,” the compound offered a picturesque reproduction of a part of Vienna known as “die Graben” as it appeared in the seventeenth century.

Running this attraction within “Echoes” were the Ladies of the Third Presbyterian Church, who showed the good people of Chicago how Old Vienna should be represented. This bevy of young women, wearing costumes of native Austrian and German girls, offered refreshments and tempting German and American dishes served at small tables.

Patrons nostalgic for the food that they had enjoyed at the 1893 Fair were pleased. The Evening Post commented that the memorable menu would be “hailed with delight” when patrons learned that the original prices, however, would not be revived with the original bill of fare. [Chicago Evening Post Nov. 13, 1893]

Those looking for a mug of beer, however, were disappointed by its exclusion. “Old Vienna without the beer,” quipped the Inter Ocean, “is a little like Hamlet without the part of the melancholy Dane. [“Donkey for a Prize”] Even without Old Vienna’s chief attraction, this new version did very well in fundraising.

Valentine Peters, night watchman of the Austrian Village on the Midway of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

The Dahomey Village

On display within the bark enclosure of the bazaar’s Dahomey Village booth were a group of nineteen African “slaves,” performed by a theatrical group known as the Kenwood minstrels.

Chicago society staged a crude caricature of the Dahomey Village from the 1893 World’s Fair, itself a multifaceted concession. In his scholarship on the black presence in the White City, historian Christopher Robert Reed describes the contradictory influences of the Dahomey Village, noting that the Fon people of west Africa “imposed an undeniable humane presence at the fair and represented a reality that could never totally be denied,” while the white press engaged in “the manipulative molding of images, both contemporarily and posthumously, to depict the Fon as savages, barbarians or cannibals.”[Reed, 146-48]

Looking back from our current era, in which the career of a politician or celebrity can be ruined by revelations of their donning “blackface” costumes, descriptions of this 1894 minstrel show are disgraceful. Gilded-age Chicago society, however, seemed to have no reservations about such racist caricatures–at least in the records left by the press. The Inter Ocean, in particular, supplied its readers with deplorable depictions of Africans in the illustrations accompanying their reports on “Echoes.”

The press reported that the Kenwood minstrels offered “fanciful and entertaining shows” that included “wild war dances, songs, and cakewalks. [“Midway is Revived”] The “hideous din of the burnt cork savages” evoked “roars of applause” from Chicago’s society set. [“Scottish Night in Midway”] About the minstrels’ attire, the Inter Ocean observed that, in the “uncomfortable warmth of the building, their simple costumes, largely composed of fresh air, were very comfortable.” [“Camel Here at Last”]

A running gag of the minstrels was to “exhibit their ferocity by eating enormous loaves of high-priced bread without butter.” [“Midway Here Again”] A “telegraph office” in a corner of the Dahomey Village supplied material for another act, in which an operator received telegrams replete with humorous saying and topical comments from dignitaries such as President Grover Cleveland, Illinois Governor John Altgeld, and Queen Victoria of England.

Jugglers in the Dahomey Village. [Image from the Chicago Evening Post, Nov. 12, 1894.]

Continuing further south along the west side of the Second Regiment Armory, patrons came to …

The Moorish Palace

One of the stranger attractions on the 1893 Midway was the Moorish Palace. The building’s exterior evoked the style of Alhambra and other old Moorish temples of Spain and North Africa while its interior offered visitors a strange hodge-podge of funhouse attractions.

Chicago’s society set dressed as Arabs “Outside the Moorish Theater.” [Image from the Chicago Inter Ocean, Nov. 17, 1894.]

“A Modernized Moor” [Image from the Chicago Inter Ocean, Nov. 18, 1894.]

Hagenbeck’s Animal Arena

Carl Hagenbeck’s Wild Animal Arena and Museum on the 1893 Midway housed a zoological arena for shows featuring lions, tiger, bears, boars, monkeys, a dwarf elephant, and much more from its menagerie.

Advertisements for “Echoes” promised that Hagenbeck and his trained animals were on hand “to delight and terrify the visitors.” [“Midway is Revived”] One newspaper confided that “how this will be done is secret,” describing the animal show as “perhaps the strangest of all the attractions.” [“The Latest Idea”] The secret of Hagenbeck’s Animal Arena was that it featured neither Herr Hagenbeck nor his trained animals.

Run by the Douglas Club with twelve performances each evening at every half hour with Prof. Carl Kreisel (or Kriesel), the Animal Arena was described in its program as: “A Wonderful Animal Show—The greatest exhibition of trained dogs every [sic] seen in Chicago. Some of the most wonderful feats of balancing, vaulting, tumbling, and trick performances ever attempted before.” [“Again the Midway”] The trained-dog show featured a woolly poodle clown dog that walked along a tight rope accompanied by little “Toby Tyler” riding on his back and a haughty pug whose performances delighted the little ones.

Walking to the center of the armory, guests could find refreshments at …

The New England Home

Emma Southwick Brinton’s New England Log Cabin and Restaurant on the 1893 Midway had offered weary visitors a comfortable restaurant with colonial-era decor and traditional New England fare.

The New England Home reconstructed for “Echoes” employed six women from the Union Park Congregational Church dressed as Puritan maidens. Along with fifteen costumed assistants, they served “ye olden tyme” refreshments and light New England fare that included doughnuts, pumpkin pie, and coffee.

Puritan women from the New England Home kitchen. [Image from the Chicago Inter Ocean, Nov. 12, 1894.]

To the northeast of the New England Home restaurant was …

The Turkish Theater

The Turkish Village of the 1893 Midway featured a Constantinople street scene with café, bazaars, mosque and minaret tower, and an “Oriental Odeon” Turkish Theater.

The theater reproduced for “Echoes” was run by Miss Anna M. Morgan of the prestigious Chicago Conservatory of Music. Men from the Chicago Athletic Club contributed the entertainment by engaging in wrestling and fencing displays while dressed as Turks. Adon Butler, American lightweight wrestling champion, successively threw about amateur wrestlers from the Club, while a dumb-bell lifter gave exhibitions of his fierce strength.

A “Turkish Theater Character” [Image from the Chicago Evening Post, Nov. 12, 1894.]

“A Group of Speakable Turks” [Image from Chicago Inter Ocean, Nov. 25, 1894.]

The “Finest Show on Midway” was a male window dresser from Marshall Field’s performing the tantalizing belly dance. [Image from the Chicago Inter Ocean, Nov. 18, 1894.]

The Chinese Theater

The Chinese Village of the original Midway Plaisance, with its Joss House and Chinese Theater, ended up being one of the poorest-performing concessions of the 1893 Fair, perhaps due to anti-Chinese sentiment at the time.

This revived Chinese Theater was run by the Marquette Club, a Chicago social club committed to promoting good government. A barker enticed visitors into the theater for a Chinese play performed by a company of twenty young men and women who were pupils of the Sopor School of Oratory. One source claimed that the actors were a “mixed company of real and fake Chinese.” [“Last Nights to Go”]

A “Chinese Bride and Groom” who performed in the wedding drama in the Chinese Theater. [Image from the Chicago Evening Post, Nov. 12, 1894.]

At the far east end of the Second Regiment Armory stood the greatest attraction of “Echoes of the Midway” …

The Street in Cairo

“More attention has been given the reproduction of the Street in Cairo than to any other part of the show,” assured the Chicago Daily Tribune.[“More of the Midway”]

Its namesake had been the most successful concession on the 1893 Midway. The picturesque enclosure that formed the Street in Cairo provided fairgoers with an interesting representation of a Cairo cityscape lined with dwellings, shops, cafes, a mosque, and a theater. For the “Echoes” bazaar, George C. Pussing, George Pangelos, and Col. Ninci, of the Egypt-Chicago Exposition Company claimed to have reproduced an “exact miniature” of their exhibit from the 1893 World’s Fair.

Visitors relived their memories of the 1893 Midway through “A Ride on the Cairo Donkey.” [Image from the Chicago Inter Ocean, Nov. 15, 1894.]

Reassembled for the revived Cairo street were materials and exhibits used in the original 1893 Midway attraction, everything from Egyptian tents to authentic admission tickets. Draping from the earlier Midway were repurposed for the bazaar. Adding to the decoration was a new theatrical drop painting by scenic artist Thomas G. Moses that “reproduced the well-known street with much care and detail.”[“Midway Here Again”]

Eight booths—named the Oriental, the Jewelry, the Perfumery, the Musical, the Shoe, the Furniture, the Coffee, and the Candy—displayed Egyptian antiques and goods for sale.

Visitors may have felt nostalgic at hearing the familiar shouts of “Bum, bum, very bum candy!” from street vendors, but “Echoes” manager Cora Scott Pond-Pope assured her society guests that the candy served here was not the original “bum bum” of the Midway, but instead fine treats from one of the Chicago’s best confectioners.

“More than 100 people will appear in Oriental garb” promised organizers of the bazaar.[“Imitate the Midway”] A cast of Chicago society women portrayed Egyptian girls, veiled flower girls, musicians, dancing girls, and saleswomen. Two men portrayed “Faraway Moses” and another two dressed as “Adonis from the Nile” while other men played fakirs, runners, ticket sellers, Cairo street “dudes,” water-carriers, candy sellers, swordsmen, and donkey boys. A fortune-teller and juggler rounded out the cast of Egyptians.

The wedding ceremony that had been performed daily on the 1893 Midway was recreated for the bazaar twice each hour by Miss Virginia Coffee and Harlan Cook, who played the bride and groom (with Miss Sarah Kimball and A. W. Curran as their alternates).

“In the Street of Cairo” [Image from the Chicago Evening Post, Nov. 12, 1894.]

Early on, organizers recognized the draw of having camels for their bazaar, so Mrs. Matilda Carse, Chair of “Echoes,” sent out a call for anyone in Chicago with knowledge of how to procure a camel to contact her. It seemed to work. The Cincinnati Zoo loaned the first “ship of the desert,” which was sent by train on November 11. Mrs. Carse met the creature at the train depot in Chicago and brought it to her home on Ashland Boulevard!

“This Was an Easy One” for the camel in the Street in Cairo. [Image from the Chicago Inter Ocean, Nov. 17, 1894.]

“Where is the poor thing raised?” asked one rider.

“He is bred in Egypt, dear” explained her companion.

“Yes; and pie in the Midway. Isn’t that clever,” she replied. [“Pie on the Midway”]

More corpulent riders from Chicago society “Broke the Camel’s Back.” [Image from the Chicago Inter Ocean, Nov. 20, 1894.]

This ends our journey through the Second Regiment Armory building. In Part 3 of this article series (“Fourteen Villages and a Jail”) we’ll explore the rest of “Echoes of the White City” inside the Battery D Armory.

SOURCES

“Again the Midway” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 12, 1894, p. 4.

“All Flock to Midway” Chicago Herald Nov. 18, 1894, p. 6.

“Camel Feeling Bad” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 18, 1894, p. 3.

“Camel Here at Last” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 16, 1894, p. 4.

Chicago Evening Post Nov. 13, 1893, p. 6.

“Children’s Day in the New Midway” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 18, 1894, p. 4.

“College Boys’ Yells” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 24, 1894, p. 7.

“Donkey for a Prize” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 25, 1894, p. 9.

“Events Planned for the Future” Chicago Daily Tribune Oct. 28, 1894, p. 36.

“Fair Ada in Silver” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 17, 1894, p. 6.

“Fun at the Midway” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 15, 1894, p. 5.

“Grand Benefit Bazaar” Chicago Inter Ocean Oct. 10, 1894, p. 8.

“Imitate the Midway” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 11, 1894, p. 7.

“Last Nights to Go” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 25, 1894, p. 11.

“The Latest Idea” San Francisco Chronicle Oct. 11, 1894, p. 1.

“The Midway Again” Chicago Inter Ocean Oct. 21, 1894, p. 8.

“Midway Closes Tonight” Chicago Evening Post Nov. 27, 1893, p. 2.

“‘The Midway’ for Charity” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 2, 1894, p. 8.

“Midway Here Again” Chicago Herald Nov. 14, 1894, p. 3.

“Midway is Revived” Chicago Herald Nov. 11, 1894, p. 6.

“Midway Makes a Hit” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 14, 1894, p. 5.

“Money Plenty on the Midway” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 21, 1894, p. 2.

“More of the Midway” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 14, 1894, p. 8.

“The New Midway” Chicago Inter Ocean Oct. 28, 1894, p. 16.

“Old Vienna in its Glory” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 23, 1894, p. 3.

“On the Midway Again” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 13, 1894, p. 3.

“On the Midway Plaisance” Chicago Evening Post Nov. 14, 1893, p. 2.

“Opening of the Midway” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 13, 1894, p. 8.

“Pie on the Midway” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 20, 1894, p. 4.

Reed, Christopher Robert All the World is Here!: The Black Presence at White City. Indiana University Press, 2000.

“Reviving the Midway” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 2, 1894, p. 8.

“Scottish Night in Midway” Chicago Herald Nov. 16, 1894, p. 11.

“Society” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 8, 1894, p. 13.

“Society” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 22, 1894, p. 8.

“White City Echoes” Chicago Evening Post Nov. 12, 1893, p. 5.

“Will Soon Be Over” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 24, 1894, p. 5.