Note: Hamlin Garland will be inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame at a ceremony on Tuesday, April 16, 2024, from 5:30—8 pm at the Chicago History Museum. Further information about Hamlin Garland can be found at the Hamlin Garland Society website https://www.garlandsociety.org/

“Sell the cook stove if necessary and come. You must see this fair.”

This oft-repeated quote, brimming with enthusiasm and promise for the 1893 World’s Fair, was Hamlin Garland’s enticement for his parents to visit him in Chicago. Often overlooked is the actual experience they had after accepting his invitation to the Columbian Exposition. The great fair was simply too much for them. After only a few hours on the fairground his mother pleaded: “Take me home. I can’t stand any more of it.”

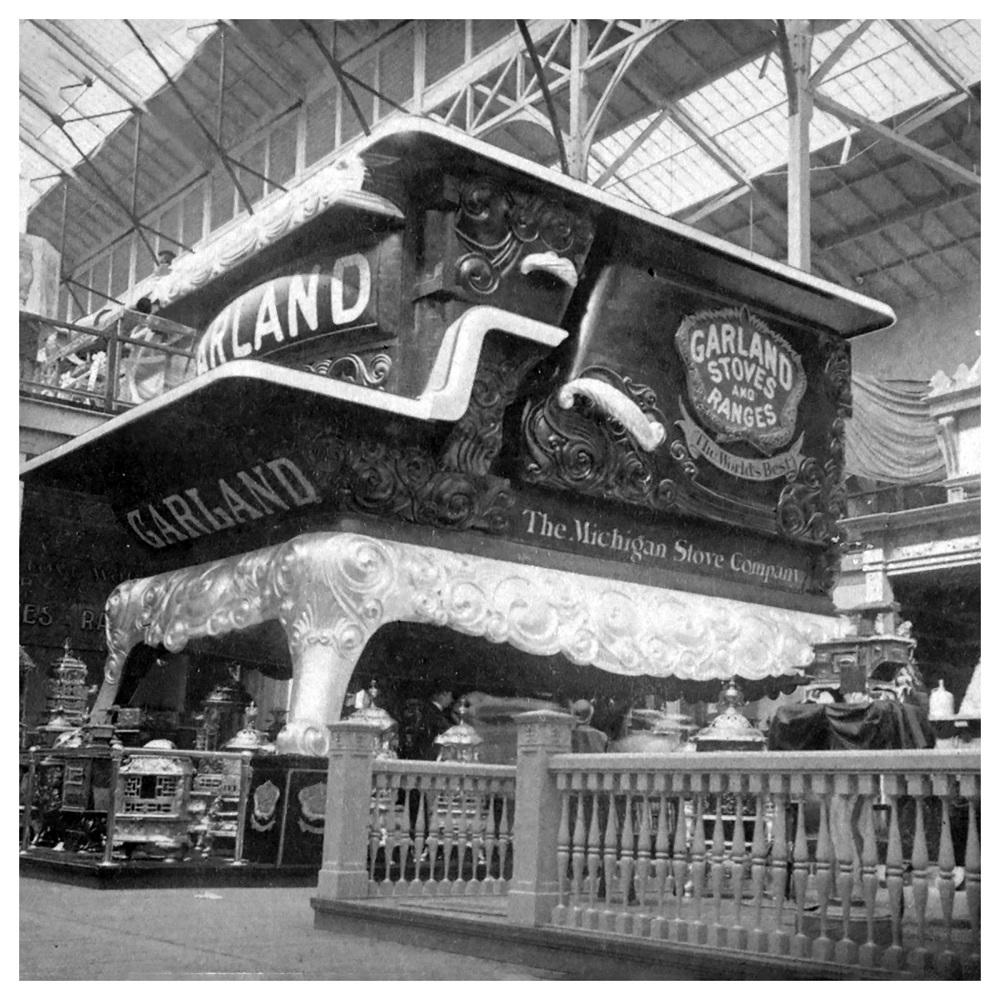

Oppressed with the exotic and the magnificent? The mammoth Garland cooking stove of Michigan Stove Company, which was on display at the 1893 World’s Fair in the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building. [Image from Strohmeyer & Wyman stereoscope card.]

In 1893, thirty-two-year-old Garland moved to Chicago, living at 6427 South Greenwood Avenue in the Woodlawn neighborhood. (A nearby playground, Moccasin Ranch Park, is named for Garland’s 1909 short-story collection Moccasin Ranch.) Just a few weeks after arriving in the World’s Fair city, he met sculptor Lorado Taft’s sister Zulime, whom he married in 1899. Also a sculptor, Zulime Taft worked in Paris with some of the “White Rabbits” from the Fair, including Janet Scudder and Bessie O. Potter.

Hamlin Garland c1892. [Image from The Arena January 1892.]

After the Columbian Exposition, Garland founded the illustrious Cliff Dwellers Club and served as its first president. (The Club’s name likely came from Henry Blake Fuller’s bestselling 1893 novel, The Cliff Dwellers, as opposed to the Cliff Dwellers exhibit at the 1893 World’s Fair). Garland still keeps watch over Cliff Dwellers from his portrait painting that hangs above the fireplace of their clubhouse on Michigan Avenue.

The handsome Cliff Dwellers Club lounge, showing the portrait of first president Hamlin Garland in a place of honor above the fireplace. The names of many influential contributors to the 1893 World’s Fair run along the frieze in the foreground. [Image from the Cliff Dwellers.]

I packed my books ready for shipment and returned to Chicago in May just as the Exposition was about to open its doors.

Like everyone else who saw it at this time I was amazed at the grandeur of “The White City,” and impatiently anxious to have all my friends and relations share in my enjoyment of it. My father was back on the farm in Dakota and I wrote to him at once urging him to come down. “Frank will be here in June and we will take charge of you. Sell the cook stove if necessary and come. You must see this fair. On the way back I will go as far as West Salem and we’ll buy that homestead I’ve been talking about.”

My brother whose season closed about the twenty-fifth of May, joined me in urging them not to miss the fair and a few days later we were both delighted and a little surprised to get a letter from mother telling us when to expect them. “I can’t walk very well,” she explained, “but I’m coming. I am so hungry to see my boys that I don’t mind the long journey.”

Having secured rooms for them at a small hotel near the west gate of the exposition grounds, we were at the station to receive them as they came from the train surrounded by other tired and dusty pilgrims of the plains. Father was in high spirits and mother was looking very well considering the tiresome ride of nearly seven hundred miles. ‘‘Give us a chance to wash up and we’ll be ready for anything,” she said with brave intonation.

We took her at her word. With merciless enthusiasm we hurried them to their hotel and as soon as they had bathed and eaten a hasty lunch, we started out with intent to astonish and delight them. Here was another table at “the feast of life” from which we did not intend they should rise unsatisfied. “This shall be the richest experience of their lives,” we said.

With a wheeled chair to save mother from the fatigue of walking we started down the line and so rapidly did we pass from one stupendous vista to another that we saw in a few hours many of the inside exhibits and all of the finest exteriors—not to mention a glimpse of the polyglot amazements of the Midway.

“In the Rotunda of the Administration Building” by T. Dart Walker depicts a visitor in a rolling chair. [Image from Harper’s Weekly Nov. 11, 1893.]

Stunned by the majesty of the vision, my mother sat in her chair, visioning it all yet comprehending little of its meaning. Her life had been spent among homely small things, and these gorgeous scenes dazzled her, overwhelmed her, letting in upon her in one mighty flood a thousand stupefying suggestions of the art and history and poetry of the world. She was old and she was ill, and her brain ached with the weight of its new conceptions. Her face grew troubled and wistful, and her eyes as big and dark as those of a child.

“The East Lagoon by Moonlight” [Image from Picturesque World’s Fair. W.B. Conkey, 1894; image digitally edited and © worldsfairchicago1893.com]

Sadly I took her away, back to her room, realizing that we had been too eager. We had oppressed her with the exotic, the magnificent. She was too old and too feeble to enjoy as we had hoped she would enjoy, the color and music and thronging streets of The Magic City.

At the end of the third day father said, “Well, I’ve had enough.” He too, began to long for the repose of the country, the solace of familiar scenes. In truth they were both surfeited with the alien, sick of the picturesque. Their ears suffered from the clamor of strange sounds as their eyes ached with the clash of unaccustomed color. My insistent haste, my desire to make up in a few hours for all their past deprivations seemed at the moment to have been a mistake.

SOURCE

Garland, Hamlin A Son of the Middle Border. Macmillan, 1917, pp. 458–460.