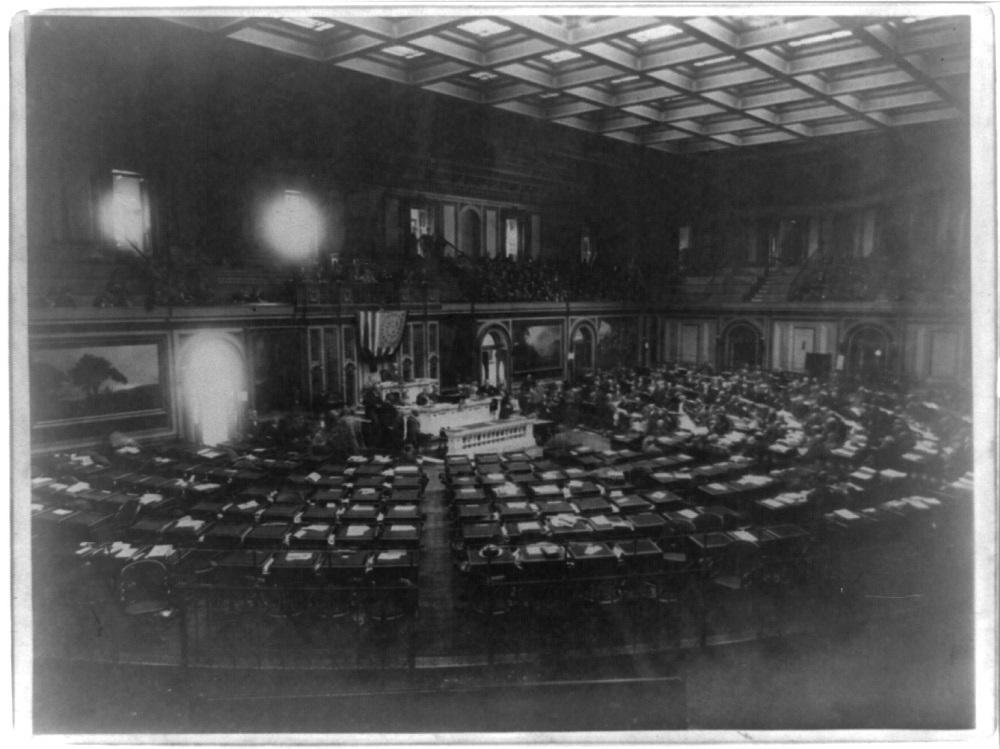

Congressmen filed into the great hall of the U.S. Capitol as the House of Representatives went into session on February 24, 1890. Just after noon, the first order of business was a vote to select a host site for the upcoming World’s Fair, then planned for 1892. Boosters from New York, Chicago, St. Louis, and Washington, D.C., packed the galleries in nervous anticipation. Support in Congress seemed to be split among the four cities vying for the honor, so no one expected a winner to emerge in this first ballot.

Interior view of House chamber during session of 51st Congress in 1890. [Image from the Library of Congress.]

Raucous Roll Call

House Speaker Thomas B. Reed (R) of Maine repeatedly warned both the gallery and the floor against any disruptions from partisan applause. Despite this, the chamber erupted in a unified roar of laughter when one vote was announced. Reed made no attempt to quell the outburst. When the roll call concluded a few minutes after 1 o’clock, no city had received the necessary majority of the 305 votes cast to win, although Chicago had garnered more votes than expected:

Chicago: 115

New York: 72

St. Louis: 61

Washington: 56

Cumberland Gap: 1

The other surprise—and the cause of the laughter—was that Cumberland Gap was in the running to host the World’s Fair!

Wait … what?

The Davenport Daily Times on February 25, 1890, reported this tally of the first ballot in the House of Representatives, with “Scattering” receiving one vote.

Who voted for Cumberland Gap?

News of the vote quickly spread across the country.

“I wonder who voted for Cumberland Gap?” asked a man with long side whiskers and a tall hat standing outside the Tribune office in downtown Chicago as he heard the news. “Some St. Louis man must have made a mistake,” replied his companion.

It was no mistake. Causing the uproarious laughter in Congress was the surprise single vote cast by Rep. Thomas Gregory Skinner (1842–1907), a Democrat serving in his third (non-consecutive) term from North Carolina’s First District. The former Confederate Army soldier ran a law practice in the town of Hertford, on the Atlantic coast near the Virginia border. Five hundred miles to the west was Cumberland Gap, a pass through the Appalachian Mountains near the point where Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee meet. Perhaps Skinner knew of Cumberland Gap because of its strategic position during the Civil War? Did he really want this to be the site for the World’s Fair?

His seemingly random nomination sparked the Los Angeles Evening Express to wonder: “Where are the supporters of Oshkosh, Saint Joe and Milpitas?” Apparently they were not in the halls of Congress.

Rep. Thomas Gregory Skinner (D) of North Carolina cast the sole vote for Cumberland Gap to host the 1892 World’s Fair. [Image from the Library of Congress.]

Cumberland Gappers

Although the location of the host site that Skinner nominated was recorded as “Cumberland Gap,” it appears not to refer to the tiny (then and now) town of Cumberland Gap, Tennessee located below the scenic pass to the southeast. The town petitioning to host the Columbian fair was Middlesborough, Kentucky, which sits one mile west of the Gap. The town (now named Middlesboro) had just opened its first post office less than two years earlier and would not be incorporated until a month after the World’s Fair vote in Congress.

A few days before the Congressional vote, the Boston Evening Transcript reported that “Cumberland Gappers” from Middlesborough, anxious to host the 1892 World’s Fair, had been making their case in a circular promoting their area and its resources. An accompanying U.S. map depicted twenty-eight million potential fairgoers living within a circle having Cumberland Gap at its exact center. That the circle stretched from Illinois to Florida may not have helped their already unconvincing case. “Doubtless consideration for effete centres of civilization such like New York and Chicago has alone prevented them from printing a circle comprehending St. Petersburg and Yokohama,” quipped the Transcript.

Imagining an 1892 World’s Fair in Cumberland Gap, Kentucky. [Image © worldsfairchicago1893.com]

The man who gazed into futurity

Others saw pluck and promise. The single vote for Cumberland Gap “will serve to call attention to that place, which is now on a big boom, with possibilities of future greatness which may result in its being selected as the site of the world’s fair at the next Centennial in 1992,” offered the Baltimore Sun, with seeming sincerity about the towns growth potential. Mr. Skinner’s vote “may one day be referred to as that of a man who gazed into futurity and saw a great city in southwestern Virginia. Chicago’s prospects 100 years ago were certainly not as rosy as are those of Cumberland gap at the present time, and still she got there.”

The Charlotte Chronicle echoed this sentiment, writing that: “Cumberland Gap may possess some advantages which Chicago has not. Land upon which to erect the buildings for the exhibition might come cheaper in the vicinity of the Gap than in Chicago … Cumberland Gap might begin to publish her advantages to the country now, with the view of obtaining the World’s Fair of 1992.”

Publish they did. In the days after the Congressional vote, newspapers across the country carried promotional articles touting a bright future for Middlesborough. The Kentucky town would become a future great manufacturing metropolis and already had earned the title of “Marvelous City,” claimed a puff piece in the Burlington Free Press. The town’s success “has attracted to it the eyes of all the financial world,” stated a bit of boosterism in the Boston Globe. The New Haven Morning Journal and Courier highlighted that the “boldest undertaking in the way of town building yet exhibited” could be found in Middlesborough, which, according to an article in the Fall River Daily Evening News, “will have a population of not less than 10,000 and possibly 15,000” by January 1891. As of 2022, barely 9,000 lived in the small city.

This promotional piece about Middlesborough, Kentucky, appeared in the Boston Globe on February 26, 1890—two days after Cumberland Gap received a single vote in Congress to host the 1892 World’s Fair.

Will go rattling down the corridors of time

How Middlesborough, Kentucky, was able to get the North Carolina congressman to cast a vote for them remains a mystery. Maybe Mr. Skinner truly believed in the promise of Cumberland Gap, or perhaps there was a kickback awaiting him? The Morganton Herald in Skinner’s home state described their (unnamed) congressman as “some member with the instincts of a real estate boomer.”

The Washington Critic failed to see prescience in the tar heel congressman’s vote. “Mr. Skinner of North Carolina is the gentleman who will go rattling down the corridors of time as the man famous for wanting to hold the World’s Fair in honor of Columbus’ discovery at Cumberland Gap,” the paper wrote with muddled syntax.

Other’s saw Skinner’s nomination of the mountain-pass town simply as a theatrical maneuver to show opposition to hosting a World’s Fair anywhere in the United States. The Chicago Tribune labeled him a “no-Fair man.” In The Devil in the White City, Eric Larson characterizes Skinner as “one congressman opposed [to] having a fair at all,” who then voted for Cumberland Gap “out of sheer cussedness.” Skinner was not alone, though. A handful of other representatives agitated, unsuccessfully, to have a choice of “opposed” added to the list of proposed host cities. Prior to the February 24 vote, Rep. James Blount of Georgia had attempted to introduce a motion hostile to the fair, but it was rejected on parliamentary grounds.

Satisfied that Cumberland Gap stood no real chance, Mr. Skinner voted for Washington on the second ballot. Not until the eighth ballot did any city receive a majority vote. The eventual winner—of course—was Chicago.

Chicago Wins! “Uncle Sam Awards the World’s Fair to the Fairest of all his Daughters” [Colorized image based on cartoon in the February 25, 1890, Chicago Daily Tribune.]

The frontier has passed by

Although Cumberland Gap did not keep their dream of a World’s Fair alive until 1992, ten years earlier an international exposition was erected just sixty miles south. Energy Expo ’82 ran for six months in nearby Knoxville, Tennessee, and surpassed its attendance goal of 11 million visitors.

Cumberland Gap had one moment in the spotlight at the 1893 World’s Fair. In his famous speech “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” for the American Historical Association Meeting in the World’s Auxiliary Congress, Frederick Jackson Turner invoked the mountain pass:

“Stand at Cumberland Gap and watch the procession of civilization, marching single file—the buffalo following the trail to the salt springs, the Indian, the fur-trader and hunter, the cattle-raiser, the pioneer farmer—and the frontier has passed by.”

What a different view that could have been if Cumberland Gap had garnered more votes in Congress in 1890.

What if …? [Image © worldsfairchicago1893.com]

SOURCES

“Chicago Gains” Washington Critic Feb. 24, 1890, p. 1.

“Chicago Gets the Fair” Morganton (NC) Herald Feb. 27, 1890, p. 2.

“Cumberland Gap’s Hope” Charlotte (NC) Chronicle Feb. 27, 1890, p. 2.

“A Happy Suggestion” New Haven (CT) Morning Journal and Courier Feb. 26, 1890, p. 4.

Larson, Erik The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America. Crown, 2003.

“A Marvelous City” Burlington (VT) Free Press Feb. 26, 1890, p. 4.

“Middlesborough as She is Today” Fall River (MA) Daily Evening News Feb. 25, 1890, p. 8.

“Next Time, Perhaps” Baltimore Sun Feb. 25, 1890, p. 2.

“On the first …” Los Angeles Evening Express Feb. 24, 1890, p. 4.

“Result of the First Ballot” Chicago Tribune Feb. 25, 1890, p. 1.

“Unfinished” New York World Feb. 24, 1890, p. 1.

“We Are the People” Chicago Tribune Feb. 25, 1890, p. 3.

“A Wonderful City” Boston Globe Feb. 26, 1890, p. 4.