Reprinted below are ten “Literary Tributes to the World’s Fair” from the October 1893 issue of The Dial, a literary magazine published in Chicago. The notable contributors are:

- Mary Hartwell Catherwood (1847—1902), Midwest author of popular historical romances, short stories, and poetry;

- Charles Dudley Warner (1829–1900), essayist and novelist best remembered as the co-author with Mark Twain of The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (1873);

- George W. Cable (1844–1925), novelist who portrayed Creole life in his native New Orleans;

- Henry B. Fuller (1857–1929), Chicago author of The Cliff-Dwellers (1893);

- Hjalmar H. Boyesen (1848–1895), Professor of Germanic languages at Columbia University;

- Harriet Monroe (1860–1936), the poet who presented her “Columbian Ode” on Dedication Day;

- William P. Trent (1862–1939), English professor and dean at Sewanee;

- Paul Bourget (1852–1935), French author and literary critic.

- Walter Besant (1836–1901), English novelist and historian; and

- Richard Watson Gilder (1844–1909), American poet who wrote a poem titled “The White City.”

Literary Tributes to the World’s Fair

No person of prominence in the literary world has, we believe, been rash enough to attempt a description of the Columbian Exposition. The special correspondents have, of course, portrayed it in a variety of aspects and in gorgeous newspaper style; and occasionally a venturesome poet has taken a shy at it in a sonnet or a quatrain. But to describe it as a whole, to realize the full vision of the White City in words and fix them in literature, is a task too formidable for any near beholder, whose brain is overwhelmed and bewildered by its own impressions. As Professor Lounsbury, of Yale, aptly expresses it: “I could no more describe the impression made upon me by the Exposition than I could pick up one of the buildings and carry it off on my shoulders. It was simply a journey into Fairyland; and I know of no one that ever lived who made a trip of that kind and brought back any adequate account of what he had seen—with the exception of Shakespeare.”

Yet there is always a special value in the word of an eye-witness, and first impressions are significant, however imperfect their expression. The Dial has lately interested itself in collecting from a number of the prominent literary people who have visited the Fair some brief comments on or characterizations of it, such as might serve to show, in some measure, the impression which the Fair as a spectacle makes on the literary mind.

In these fragmentary but often felicitous expressions, which are given below, there will be found much that is of interest. The reserve shown by these practised writers befits the vastness of the theme; they prudently refrain from attempting to exhaust either the subject or themselves. Possibly some less experienced and more enthusiastic writers may find a hint here worth the noting. The best writers do not “gush,” or depend overmuch on adjectives, even when writing of a Columbian Exposition.

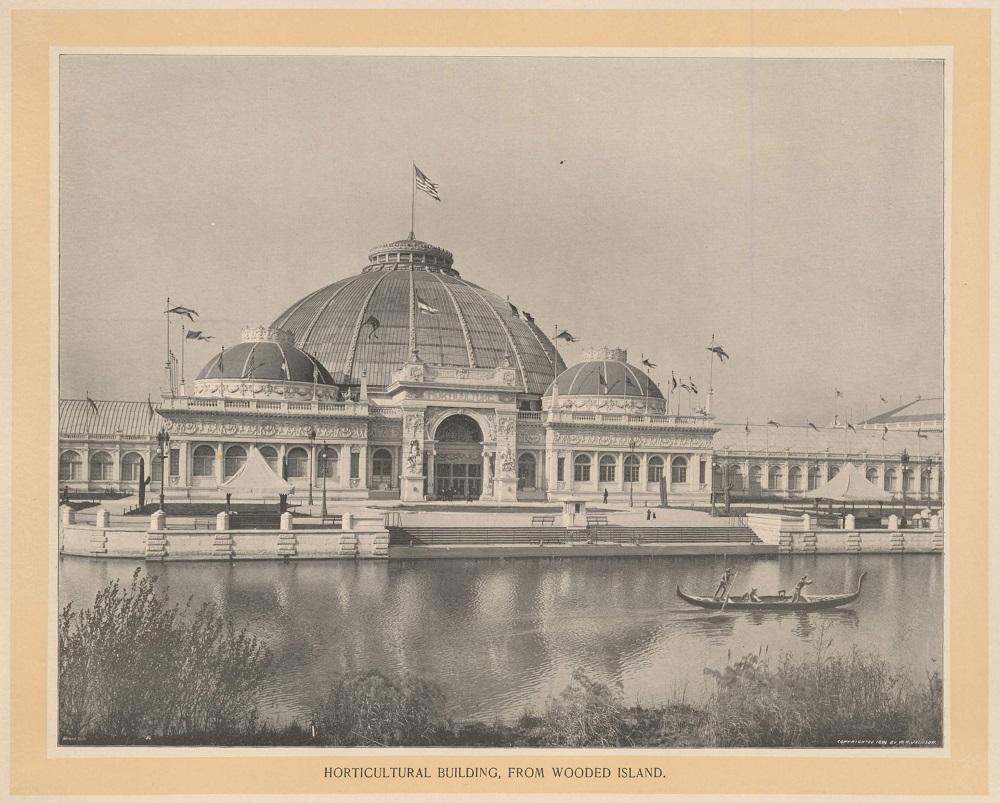

Horticultural Building, from Wooded Island. [Image from Jackson, William Henry, Jackson’s Famous Pictures of the World’s Fair. White City Art Co., 1895.]

MARY HARTWELL CATHERWOOD

Mrs. Catherwood’s contribution so admirably reflects what is doubtless the dominant impression made by the Exposition upon imaginative minds—the impression of magical and bewildering beauty, tinged with sadness at its transitoriness—that we gladly place it at the head of the collection.

The more I see of the Fair the more I want to see of it. I long to wake up there and get its aspects in the early morning; and to haunt it when the lights are turned off after midnight. It is not like any other country I have ever seen. As soon as you become a day-inhabitant of the White World, you are emancipated from the troubles of earth. It has a strange effect. I am all the time conscious of deep pity for any human being who loses the sight of it. One of its strangest influences is stripping you of the sense of locality. I can find my way anywhere on the crust of the globe ; but in the Fair I give it up. Geography may go by the board. I take with thankfulness the place which comes nearest to me, and my head whirls, and the Plaisance moves from side to side in its usual game of hide and seek.

So fascinating is the environment there that I never expect to learn anything from the exhibits: there is no time. Some day I shall mourn lost opportunities. But mortals cannot do everything. And one can expand his knowledge and take a world-bath in Jackson Park now by merely sitting still and watching the nations pass by.

One question I dare not face: What shall we do when this Wonderland is closed?—when it disappears—when the enchantment comes to an end.

The Fisheries Building. [Image from Jackson, William Henry, Jackson’s Famous Pictures of the World’s Fair. White City Art Co., 1895.]

CHARLES DUDLEY WARNER

Mr. Warner’s word is for use rather than beauty—rather, perhaps, for the usefulness of beauty.

I think that those who were most familiar with the finest architectural effects abroad were most astonished at the aesthetic side of our World’s Fair. It was wholly unexpected. But the impression upon the great public of the United States of this incomparable vision of beauty is more important. The sight of it has changed the world, has changed the aspect and the estimate of life, for tens of thousands of home-keeping people. It has introduced into practical lives the element of beauty, and opened a new world of enjoyment.

The extent of this transformation grows upon me, since I visited the Fair, in conversation with others, and in letters I have seen from all parts of the Union, which speak of what the spectacle at Jackson Park has done for the writers. I do not mean in regard to the competing exhibits—those have their separate educating influence,—but to the quickening of the imagination, and the enlargement of the appreciation of beauty. It is no criticism upon the people of the United States, absorbed in material development, to say that they needed just such an uplift. If it cannot be called a spiritual influence, it is an aesthetic impulse that leads away from materialism.

Golden Door of Transportation Building. [Image from Jackson, William Henry, Jackson’s Famous Pictures of the World’s Fair. White City Art Co., 1895.]

GEORGE W. CABLE

Mr. Cable, too, finds in the Fair a great and permanent educating influence, well worth its cost.

I consider that notwithstanding any supposable money loss to those who have invested their funds in the Fair, it is nevertheless one of the best investments the city of Chicago has ever made. It has lifted her status in the national estimation and declared her the first of American cities. The higher values of the Exposition it would be pleasant to predict, but they must be left for time to prove. I believe time will show them to be vast. The educative and stimulative effect to hundreds and thousands of the people of our nation will be incalculable. As a single instance, I think we may look with confidence for a great salutary effect upon the public architecture of our country.

Statue of Industry. [Image from Jackson, William Henry, Jackson’s Famous Pictures of the World’s Fair. White City Art Co., 1895.]

HENRY B. FULLER

Mr. Fuller’s thought is also of the great good the Fair will do Chicago.

Chicago, having been in the world for some fifty or sixty years, is now finally of it. Instead of merely being connected by rail, water, and wire with the various great centres of the world, it is on the point of becoming a great centre itself—not merely commercial, but financial, social, political, artistic, educational. The West is leaving the provincial standpoint which, not long ago, was that taken by the country generally: the idea that we are big enough and strong enough and successful enough to live our own detached life according to our own isolated standard.

Some few remnants of this narrow notion still linger: the bumptious Western objection to making over our ministers at foreign courts into ambassadors, and the monstrous far-western belief that we may maintain a monetary standard of our own that contravenes the general understanding of Christendom. The Fair, in fine, has brought the world to us, and sent us out into the world, and given us a chance to “heft” it, and to find our place in it, and to establish intelligent and intelligible relations with it.

The 30th of October, 1893, will be Chicago’s graduation day. And the World’s Columbian Exposition will be found to be no mere “business college,” qualifying us narrowly for a narrow life and its narrow purposes, but a real and broad university one to advance us in the arts, the sciences, the amenities, the humanities.

White City at Midnight. [Image from Jackson, William Henry, Jackson’s Famous Pictures of the World’s Fair. White City Art Co., 1895.]

HJALMAR H. BOYESEN

Prof. Boyesen sees in the external features of the Fair the realization of some glorious dream.

The Fair is the completest and most magnificent resume of the world’s work and thought that ever has been gathered in one place. In its external aspect it is a vision of delight unrivalled on this side of Fairyland. To describe the beauty of the electric illumination at night is beyond the capacity of any language. It is as if some bold spirit had dreamed a glorious dream which by enchantment had petrified into reality.

MacMonnies’ Fountain, from Grand Plaza. [Image from Jackson, William Henry, Jackson’s Famous Pictures of the World’s Fair. White City Art Co., 1895.]

HARRIET MONROE

Miss Monroe, whose “Columbian Ode” was the literary feature of the opening of the Exposition, has given a later impression, happily condensed into a sonnet.

I saw a water-lily rise one morn,

White, wondrous, and above the level blue

Unveil her virgin petals to the dew

And fill her heart with sunlight. She was born

Of royal race, to reign and to adorn.

O’er the wide world the joyous tidings flew,

And all the nations came with treasures new

To praise her loveliness, and weep forlorn.

For from the host went forth a mighty sigh

That ere the falling of a summer sun

The dream must pass, the splendor fade away.

Yet knew I well her beauty could not die.

When she hath gone her power is but begun:

Death sends the soul to God’s eternal day.

Agricultural Building, from Colonnade. [Image from Jackson, William Henry, Jackson’s Famous Pictures of the World’s Fair. White City Art Co., 1895.]

WILLIAM P. TRENT

Another felicitous sonnet comes from Prof. W. P. Trent, of Sewanee College. “It was written,” says the author, “one sleepless night at my hotel in Chicago, after a day at the Exposition. It is at least an unfeigned and spontaneous tribute to what I believe to be the most beautiful thing in all the world—a thing that we call ‘The White City,’ but for which no name is fitting or sufficient.”

Where once the red deer, chased by wily foes,

Sought the broad bosom of the peaceful lake,

Behold a noble city bloom and break

Into a flower of beauty! It arose

As though from some enchanter’s wand, and glows

With supernatural splendor. Angels take

Shy glimpses from the sunset clouds that make

The only rivals that it fears or knows.

O fair dream-city of the fruitful West—

Fair as the splendid visions that appeared

To Prospero’s companions, and confest

To be as frail,—thou yet shalt live ensphered

In every grateful memory that hath blest

The minds that planned thee and the hands that reared.

South Colonnade. [Image from Jackson, William Henry, Jackson’s Famous Pictures of the World’s Fair. White City Art Co., 1895.]

PAUL BOURGET

M. Paul Bourget, the French novelist, gives a few unstudied observations.

The Fair is like Chicago. … I have only the general first conception of a vast wilderness of beauty. Vast, big—more than any description could carry. It is wholly unlike the Paris Exposition. The two could hardly be compared. There are no common points of similarity; they are not of the same kind. This is the more wonderful by far—greater in expectation and realization, but American, typically so. That such a great city of white beauty should have been reared from level areas of wooded waste is a miracle. … The effect of the water—the artificial waterways, I mean—is surpassingly beautiful. But I am attempting to speak of what has struck me dumb with wonderment.

Midway Plaisance, Looking West. [Image from Jackson, William Henry, Jackson’s Famous Pictures of the World’s Fair. White City Art Co., 1895.]

WALTER BESANT

From Mr. Besant’s “ First Impressions of the Fair,” as printed in The Cosmopolitan magazine, we make the following characteristic extracts:

When the visitor happens to be a literary man, one who is in the habit of writing and speaking of things offered to the public, he wanders about the courts and galleries of the Exposition oppressed, far more than the inarticulate person, by the vastness of the subject. To such a man the great truth that he cannot say anything adequate and that he need not try, falls upon his spirit, when it is once grasped, like a cool shower on a hot afternoon. It lends a new and quite peculiar charm to the show. …

The bigness of the World’s Fair first strikes and bewilders—one tries in vain to understand it—and then it saddens. I observe that most people, like Xerxes, set down their tears to the evanescent nature of the show. … Then again, the Poetry of the thing! Did the conception spring from one brain, like the Iliad? Were these buildings—every one, to the unprofessional eye, a miracle of beauty,—thus arranged so as to produce this marvellous effect of beauty by one master brain, or by many ? For never before, in any age, in any country, has there been so wonderful an arrangement of lovely buildings as at Chicago in the present year of grace. …

Those English travellers who have written of Chicago dwell upon its vast wealth, its ceaseless activity, its enormous blocks of houses and offices, upon everything that is in Chicago except that side of it which is revealed in the World’s Fair. Yes, it is a very busy place; its wealth is boundless; but it has been able to conceive somehow, and has carried into execution somehow, the greatest and most poetical dream that we have ever seen. Call it no more the White City on the Lake; it is Dreamland. Apollo and the Muses, with the tinkling of their lyres, drown the bells of the train and the trolley; the people dream epics; Art and Music and Poetry belong to Chicago; the hub of the universe is transferred from Boston to Chicago; this place must surely become, in the immediate future, the centre of a nobler world the world of Art and Letters.

“Statue of Liberty” (Statue of the Republic). [Image from Jackson, William Henry, Jackson’s Famous Pictures of the World’s Fair. White City Art Co., 1895.]

RICHARD WATSON GILDER

To the foregoing brief but expressive tributes we are very glad to add Mr. R. W. Gilder’s beautiful poem written for the October Century and printed here from an advance copy kindly furnished by him. It is an eloquent expression of the feelings awakened in contemplation of the early disappearance of the Exposition, and is called “The Vanishing City.”

Enraptured memory, and all ye powers of being,

To new life waken! Stamp the vision clear

On the soul’s inmost substance. O let seeing

Be more than seeing; let the entranced ear

Take deep these surging sounds, inweaved with light

Of unimagined radiance; let the intense

Illumined loveliness that thrills the night

Strike in the human heart some deeper sense!

So shall these domes that meet heaven’s curved blue,

And yon long, white imperial colonnade,

And many-columned peristyle endue

The mind with beauty that shall never fade:

Though all too soon to dark oblivion wending,—

Reared in one happy hour to know as swift an ending.

Thou shalt of all the cities of the world

Famed for their grandeur, ever more endure

Imperishably and all alone impearled

In the world’s living thought, the one most sure

Of love undying and of endless praise

For beauty only,—chief of all thy kind;

Immortal, even because of thy brief days;

Thou cloud-built, fairy city of the mind!

Here man doth pluck from the full tree of life

The latest, lordliest flower of earthly art;

This doth he breathe, while resting from his strife,

This presses he against his weary heart,

Then, wakening from his dream within a dream,

He flings the faded flower on Time’s down-rushing stream.

O never as here in the eternal years

Hath burst to bloom man’s free and soaring spirit,

Joyous, untrammelled, all untouched by tears

And the dark weight of woe it doth inherit.

Never so swift the mind’s imaginings

Caught sculptured form, and color. Never before—

Save where the soul beats unembodied wings

‘Gainst viewless skies—was such enchanted shore

Jewelled with ivory palaces like these:

By day a miracle, a dream by night;

Yet real as beauty is, and as the seas

Whose waves glance back keen lines of glittering light

When million lamps, and coronets of fire,

And fountains as of flame to the bright stars aspire.

Glide, magic boat, from out the green lagoon,

’Neath the dark bridge, into this smiting glow

And unthought glory. Even the glistening moon

Hangs in the nearer splendor.—Let not go

The scene, my soul, till ever ’t is thine own!

This is Art’s citadel and crown. How still

The innumerous multitudes from every zone,

That watch and listen; while each eye doth fill

With joyous tears unwept. Now solemn strains

Of brazen music give the waiting soul

Voice and a sigh,—it other speech disdains,

Here where the visual sense faints to its goal!

Ah, silent multitudes, ye are a part

Of the wise architect’s supreme and glorious art!

O joy almost too high for saddened mortal!

ecstasy envisioned! Thou shouldst be

Lasting as thou art, lovely; as immortal

As through all time the matchless thought of thee!

Yet would we miss then the sweet piercing pain

Of thy inconstancy! Could we but banish

This haunting pang, ah, then thou wouldst not reign

One with the golden sunset that doth vanish

Through myriad lingering tints down melting skies;

Nor the pale mystery of the new-world flower

That blooms once only, then forever dies—

Pouring a century’s wealth on one dear hour.

Then vanish, City of Dream, and be no more;

Soon shall this fair Earth’s self be lost on the unknown shore.

“Literary Tributes to the World’s Fair” The Dial, Oct. 1893, pp. 176–78.