The short story reprinted below is a romance set on the Midway Plaisance of the 1893 World’s Fair. Writing as “A. B. Ward,” Mrs. Alice Ward Bailey (1857–1922) was a prolific author of fiction around the turn of the twentieth century. The mawkish prose and bumpy pacing in this story may explain why the author is essentially forgotten today. Still, her dramatic sketch offers an intimate peek into the lives of fictional inhabitants of the Midway and invites us to wonder about the thousands of real Midway residents whose histories from the summer of 1893 were rarely documented.

“A Medley of the Midway Plaisance” appeared in the December 1893 issue of Outing: An Illustrated Monthly Magazine of Sports, Travel and Recreation and later was reprinted in a collection of short stories from that magazine under the title The Luck of a Good for Nothing and Other Stories (Outing Pub. Co., 1895).

Much of the story takes place in the compound of the Captive Balloon Ride on the Midway. The fictional characters populating the attraction are:

- Alma Read, manager of the Captive Balloon kitchen and café

- Sydow, pianist at the café

- Letty Anderson, dishwasher

- Professor Peter Leigh, cigar-stand clerk

- “Professor” Ives, aeronaut and manager of the Captive Balloon Ride

- Mademoiselle, singer at the café

- Manuelita, dancer at the café

- Tom, Jake, and Sam, waiters at the café

- Mina, Fritz, Irma, and Gertrude Van Holst

Bailey’s general descriptions of the Captive Balloon are accurate. In addition to the aerial ride in the central courtyard, the park offered a restaurant and concert hall in the exterior structure, as described in the story. Instead of “Professor” Ives, French aeronauts handled the airship “Chicago,” which was a hydrogen-filled (not hot-air) balloon, while a former Cook County Deputy Sherriff managed the concession. The ticket price for balloon ride really was two dollars (the equivalent of roughly $65 in 2022), making this the most expensive attraction inside the fairgrounds, which cost only fifty cents to enter. (For the record, the ticket price did include the return trip to terra firma!) The aerial attraction lasted for only a month after its inaugural ascent on June 11. A powerful wind storm passing through the Midway Plaisance on July 9 ripped the balloon from its moorings and tore it to pieces. Bailey alludes to this demise in the final section of her story but moves the time to mid-August.

Several other details indicate the author’s familiarity with the fairgrounds. Baily notes several other attractions on Midway Plaisance: the Javanese Village, German Village, Dahomey Village, Old Vienna, Street in Cairo and Temple of Luxor, and the famous Ferris Wheel. The order in which characters encounter various attractions has reasonable agreement with the layout of the Midway. Bailey mentions the Convent of La Rabida and the Wooded Island. Her description of a building in the White City that is wreathed in “winged forms” is the Transportation Building, with its beautiful, winged figures decorating the spandrels. The “huge, placid cattle upon the brink guarded their own repose” likely refers to the Bull with Maiden sculptures along the Grand Basin. Finally, her invented name of “Sydow” for the German pianist is quite similar to that of Eugen Sandow, the famous Prussian “strong man” bodybuilder who performed at Florenz Ziegfeld Jr.’s Trocadero in downtown Chicago during the summer of 1893.

A MEDLEY OF THE MIDWAY PLAISANCE

By A. B. Ward

The captive balloon was of less importance financially than the restaurant. Few ventured into it, although invariably tempted to a nearer view of the gigantic brown forehead, peering grimly over the placarded walls. “How big is it?” they would ask, lounging around with their hands in their pockets. “How long are the ropes?” “Two dollars, you say, to go up? Does that cover the round trip?” And they usually walked away as they came. But almost no one escaped out of the restaurant without some expenditure, for the waiters were the hardiest set on Midway, and when they scowled at a man and asked him what he would have, it required considerable courage to answer “Nothing.”

If Mrs. Read—or “Mis. Sread,” as they called her—happened to be about, the waiters were more courteous. In fact, everything went pretty much as Alma Read directed, at the sign of the Captive Balloon. She controlled the kitchen and the café, bought the provisions, bullied the cook, and kept the dish-washers from mobbing the newest of their number, Letty Anderson, whom they pecked at as barnyard fowls peck at a swallow because she was so evidently out of her sphere. “You don’t know what you are going into,” Alma Read had told her, when she presented herself for a position, the atmosphere of her country home clinging to her neat skirts and carefully braided hair.

“I am determined to see the Fair, cried the young enthusiast,” and I am ready to do anything. I couldn’t see it without working; I haven’t the means.”

“There are a lot of your kind here,” said Alma Read, smiling kindly at Letty; and there were. One saw them everywhere—pushing chairs and taking charge of exhibits if they were men and selling baubles in the booths if they were women. They looked tired and white and bored. One questioned if they were getting more than the commercial aspect of the Fair. And dish-washing!

“But I have a college professor out at the cigar-stand,” said Alma Read. “‘Professor Peter Leigh,’ his letters come directed to him. He belongs in a college somewhere out West. He came in one day and asked for work. I told him I wanted a night porter. ‘But,” said I, ‘can you stand it to be called Peter, to be sworn at and ordered around?’ He said he could, and he came on duty that night at eight o’clock, put on his calico jumper and overalls, performed his duties and made no complaint, like the gentleman he is. As soon as there was a vacancy out there I popped him into it.”

While she talked, Alma Read watched the face of the little girl, flushing and brightening with sympathy for Professor Peter Leigh in his sacrifice of personal dignity to the Fair.

“That’s just the way I feel,” Letty responded eagerly. “I am ready for anything.” So she tucked up her sleeves, put on a gingham apron, and washed beer-mugs and sandwich-plates all day long.

There were other dramatis personae on the boards of the Captive Balloon: “Professor” Ives, the aeronaut, who managed the concern; Mademoiselle, shaking her curls as a poodle shakes his ears, to emphasize the wit of her coquettish songs; Manuelita, dancing the color out of her cheeks and the sparkle out of her large dark eyes at an hour when she should have been in bed, poor child! the Mexican boys, in velvet trousers, embroidered jackets and sombreros, playing their sweet, melancholy songs with a far-away, homesick look; and Sydow, the pianist, bringing drawing-room manners and a stiff, martial bearing into the midst of the informalities of the tent. The waiters hated Sydow, the troupe called him a “queer duck;” and Alma Read took him under her able protection, until by a fillip of Fortune’s finger he became the hero of the place, instead of the object of its ridicule and scorn.

But that was later in the season; now, when July was scorching the grass along the Plaisance and the business of being amused had become a serious affair, when even the farmers who drifted into the tent were critical of the songs and dances and “calkerlated that two dollars was a pile o’ money to pay for resken life and limb in thet balloon,” and when bad temper had accumulated like electricity, Sydow’s long, grave face and spectacled eyes, and the close-fitting black-silk cap which he never removed, were the signal for all sorts of irregularities.

“That German chap ’ll have to knock down one or two of those waiters if he wants to get along,” drawled the aeronaut, lounging up to the decorated pen where Alma Read was straightening out the accounts of the curly-headed cash girl.

“In just a minute, Mr. Ives,” said Alma, abstractedly. “You say the gentleman gave a five-dollar gold piece?”

“Yes’m, and got no change, and he thinks Tom has it.”

“I’ll take your place here for an hour and you keep out of sight. Tom ’ll bring it up here to change it, if he has it. Now, Mr. Ives—” but the aeronaut had lounged away.

With clear gray eyes, which saw everything without seeming to see, Alma watched the rows of little tables and the figures that went to and fro.

Sydow, after a series of wordy arguments with Jake, in which the latter persistently misunderstood him, had obtained a sandwich, over which he brooded with the mournfulness of a raven, his black cap drawn low on his brows. The troupe were lunching noisily at another table; and at still another the Mexicans toyed disdainfully with their knives and forks. “I must get those boys some curry,” mused Alma. “Ah, there comes Tom.”

Affecting indifference, the white-aproned waiter swung up to the window and flung a coin on the desk. Alma looked up from the book in which she was writing. A swift glance shot from her eyes into his. He turned without a word, took off his apron, and precipitately left the hall.

“D’ye get it ?” asked the cash-girl, coming up.

“D’ye get it?” echoed Mr. Ives over her shoulder.

For answer Alma held up the coin.

“How in the world did you do it? How did you know he had it?” asked the aeronaut, walking by her side down the hall.

“I was once a private detective,” answered the woman quietly. “Excuse me, now, unless there is something in particular. I’ve promised to let Miss Anderson out of the kitchen for an hour with Professor Leigh.”

“The little dish-washer? I thought so. Good-bye,” and the aeronaut sauntered back to his idle air-ship.

Like turns to like, everywhere; most of all when surrounded by differing elements. Before Letty Anderson had been bound to her soapy altar a day, her fellow-victim in the court had found her out and had determined to send her home if she would go; if not, why then he would make it as pleasant for her as possible. And how pleasant that was, only those young men and women know who varied their tasks at the Fair by visits to galleries and museums, who saw, together, the Convent and the Wooded Island, took gondola rides under the moon, and heard the German students sing in the streets of old Vienna. Not on the tennis-field or in the ballroom does companionship become most delightful, but where the finer vibrations of the spirit accompany the tingling of the nerves. Peter had his reward. He heard himself called Professor in a tone which went with the title, he was inquired of concerning things abstruse and profound, and he resumed his role of instructor with a pupil who invited instruction. When the two put the Captive Balloon behind them and went out to see the Fair, none would have dreamed that the bright face of the girl had been lifted from a dish-tub, or that the boy was he who regarded the world so fiercely from the cigar-stand.

The story of Tom and the gold piece had gone from kitchen to court, and Professor Leigh commented upon it to Miss Anderson as they walked up Midway.

“She certainly is a remarkable woman,” he said with an apologetic inflection. “The way she manages that crowd beats Hagenbeck with the tigers.”

“She told me she was the daughter of a jailer,” said Letty, “and that she had learned how much power there is in the human eye.”

“Did she?” exclaimed Peter. “She told me she had been a professional nurse, and I heard her say to Mademoiselle that she was on the stage at one time.”

“She may have been all three,” said Letty. “But I am surprised that she is satisfied to be in such a place as that.”

“Perhaps she isn’t,” said Peter quizzically. “Are you?”

Letty laughed with a blush at her own inconsistency. There was a pause, and then the professor mounted the metaphorical rostrum always at his command and began to explain the continuous arch of the Ferris Wheel.

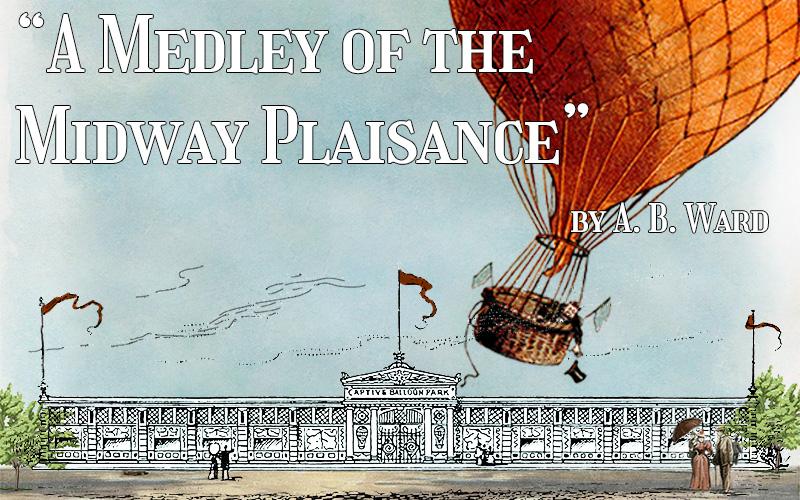

The Captive Balloon Restuarant, where the main characters of “A Medley of the Midway Plaisance” live and work.

Meanwhile, the glaring day softened into twilight, and twilight vanished at the rising of the moon. In the tent of the Captive Balloon the glasses clinked merrily. Mademoiselle, in a vivid yellow dress, sang a song, “The Midway, the Midway,” with the shrill re-iterance of a cicada; and Manuelita pirouetted bravely and shook her ribboned tambourine. Following and sustaining them, Sydow set his supple fingers to the keys; his figure seemed held erect, as the balloon was held by its cables—at least that was what Alma thought, looking on. And having nothing better to do she went out to verify her simile by comparison.

There was no one in the yard. The black engines glistened in the moonlight, the board walks leading to the dressing-rooms of the miniature theatre were white as snow. Poised on its web of cables, the balloon seemed bigger and more alive than ever. She tiptoed over the ropes and seated herself in the basket, which swayed and rocked beneath her. She made a picture in this unique setting, and realized a lukewarm regret that there was none to see.

The door of a dressing-room opened softly, but it was only Sydow. His near-sighted eyes failed to find her as he advanced stiffly down the walk. He believed himself to be alone. When he was so near that she might have touched him, he paused and looked up into the sky. “Ach, mein Gott!” he exclaimed, and sighed piteously, pushing back his cap. The moonlight fell full upon him, and there flashed into sight the outline of a silver cross set into his forehead. “Mein Gott!” he cried again, then drew on the cap and went back as he came.

Alma arose and left the car, determined to solve the mystery, but whether as the jailer’s daughter in pursuit of a culprit, or a detective following up a clew, or a nurse filled with pity for a suffering man, she herself could not have told.

As she entered the tent, she saw Sydow leaving it by the main entrance and, keeping him in sight, she threaded her way through the crowd.

Outside all was gay and bright. The arc-lights mocked the midsummer moon riding high in the heavens, for it was past eleven. Countless lanterns of various hues were strung, like Aladdin’s jeweled fruit, along the way. The visitors had left the street to its occupants, who came pouring out of their close quarters to enjoy the night: dwarfish Javanese women in scanty garments, tall, striding Arabians in flowing draperies, turbaned Turks and Armenians, Indians with long, straight hair, and Persian matrons daintily clad. Tinsel glittered and soft tints brightened as their wearers passed under the lights. The air was full of chattering talk and good-humored laughter. Above their heads the great wheel defined itself against the sky, and on all sides, tower and minaret and floating banner mingled in the conglomerate of a restless dream.

Sydow hurried on, under the low bridge and across the wide, free spaces of the Exposition grounds. Before him the tall buildings loomed, ghostly white. To the winged forms which wreathed them, the wanderer turned as if beseeching them to take on the human helpfulness they simulated.

How still it was! Smooth as a mirror lay the waters of the lagoon, unbroken by an oar; and the huge, placid cattle upon the brink guarded their own repose. Baring his brow, Sydow stepped out under the open sky. A groan escaped him. With his upturned, yearning face, sealed with the silver cross, he might have been some martyr-saint, praying with clasped hands.

Gliding from the shadow, Alma advanced and laid her hand upon his arm. For an instant his brain reeled. In her light dress, with her shapely, uncovered head, she might have stepped down from some cornice or pediment near, as pitying statues used to do in the days when men were not dependent solely on their own poor efforts, or the scanty help they get from one another.

Seeing his perturbation, she called him by name, and he recognized her with a laugh which was almost hysterical. “What is it, Sydow?” she repeated soothingly. “What troubles you? Tell me and let me help you.”

“I am the most unhappy one alive,” he sighed, “and none can help me.”

“How do you know that?” she answered briskly. “Come, sit down on this bench and tell me all about it. What have you done ? How did you get that mark on your forehead?”

There is no more wholesome treatment for morbidness than the assumption of its absence. Dropping his melodrama, Sydow answered in a voice almost as matter-of-fact as her own: “That was gif me in my own country on account of a girl; that was gif me by her cousin because I try to see her. She luv me and I luv her, and they would not haf it so, and Fritz, her cousin, haf some words with me and gif me this.” He took off the cap altogether and permitted her to scrutinize the plate covering the fracture in his forehead.

“Queer that it should be just in the shape of a cross,” she mused, examining it with the critical eye of a surgeon.

“It is a token,” cried Sydow; “the cross is on my life. I must suffer and be alone all my days.”

“Pshaw!” said the woman coolly. “You are too sentimental. Go on, what next?”

“What next?” repeated Sydow, bewildered.

“What did you do next? How long ago did this happen?”

“Fife years,” said Sydow; “and I haf been so unlucky—ever’ting against me.”

“You haven’t been here, in this city, all the time?’’

“No; I play with an orchestra in New Yo’k; the violin is my instrument; I play with ———” and he named an orchestra known to all who know such things.

“How did you lose your place?”

The questions came so quietly, yet with such authority, that there was no resenting them or withholding an answer.

“I behafe bad,” he answered with the simplicity of a child. “I haf been a fool like ever’ting. I get so discouraged, and I want my Mina.” The spectacles over his eyes were foggy as he looked at her.

“If you really want her,” said Alma with severity, “why don’t you save your money and go back and get her?”

“They won’t let me haf her, don’t I tell you ?” he cried passionately.

“Humph!” said the woman before him. She rose and stood up, tall and strong in the moonlight. “If I were a man,” she said deliberately, and stretching out one rounded arm in emphasis as she spoke, “if I were a man and knew that the woman I loved loved me, no power on earth should keep me away from her.’’

Sydow sprang to his feet, his face aflame. “And so it shall not,” he shouted. “I will work, I will go, I will claim her. Ah, thou hast spoken good words to me this night.” Before he had concluded, she was gone, passing swiftly between the buildings, across the parks and into Midway, now almost forsaken.

The night porter greeted her as she entered the tent of the Captive Balloon, but she gave no sign of hearing him. Like one pursued she traversed the hall and entered the tiny room she called her own. There she sank upon the couch and covered her face with her hands. Hour after hour she sat thus, with that immobility which does not denote calm, but the tenseness of an inward struggle. When the white light of the moon began to be infused with the flush of sunrise she arose and unlocked a small trunk, standing in the corner. Her hands did not tremble, but there was an eagerness in their groping like that of one who hungers and reaches out for bread.

The picture which she pulled out from among the piles of clothing was a photograph of a man who might have been twenty-five or less. The light of youth had not faded from his fine, dark eyes. The power of youth and its confidence were in the proud poise of the head and in the alertness of every feature. Long and earnestly she studied it, with a strange, inscrutable smile. Outside, the clatter of dishes, the tread of feet and loud talk, mingled with a ringing oath or two, announced the opening of the restaurant. The refined face before her appeared to frown at the vulgarity and the din.

“No, you never could stand it,” she said, shaking her head, the smile still on her lips.

She replaced the picture carefully in the trunk and turned the key. Except for a hint of shadow under her eyes no one would suspect her vigil. Years ago, she had taught herself to endure and show no sign. The desperate men who carried trays to the tent of the Captive Balloon had hearts of wax compared with hers. Yet she kept her cheeks of cream, while upon their physiognomies “you could have cracked a nut,” as the saving goes.

“The Midway Plaisance” watercolor by H. D. Nichols. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

To search for some particular person in that multitude seemed hopeless, as many realized who, at one time or another, lost their grasp upon a companion in the crowd. To come hither, purposing to find someone, without an appointed place of meeting, without even a clew to the whereabouts of the individual, was madness. And yet of just such madness was Miss Van Holst guilty when she accepted her uncle’s invitation to visit America and the Exposition, together with his daughters Irma and Gertrude, and his son Fritz. Was not Hermann in America? And were not all the world to be at the Fair? So Mina threw off the melancholy which had oppressed her, and was so exacting about the becomingness of her traveling gown that her aunt and cousins whispered behind her back, “She has forgotten him.”

Forgotten him! It seemed to Mina that her tell-tale heart would betray itself by its loud beating when she followed her uncle and cousins through the turnstile of the Exposition grounds and gazed at the sunny splendor of the halls beneath whose arches she expected to find her lover. As the days went on, however, and among the thousands whom she met the longed-for face did not appear, the high white buildings took on a cold, forbidding look, and from the multitudinous treasure which they held she turned with loathing. In vain Irma and Gertrude called her to admire this and that; in vain Fritz pestered her with attentions; they could not rouse her from her apathy.

“The child needs amusement,” said her uncle. “My own head whirls with trying to take in the sights. We will go down to Midway and have a good laugh.”

And to Midway they went: to the innocent gayety and the monotonous music of a Javanese wedding; to a homelike German cottage, out of whose small-paned window Mina stared with a white, desperate face, while the rest exclaimed over carved chairs and curious dishes; to Cairo street, where Irma and Gertrude mounted a camel and screamed with laughter as it strode along, where Fritz hung his long legs over a donkey to run races with an American youth who cried “Sick-em!” to his knowing little beast.

Everyone laughed—everyone but Mina, who waited, dejectedly, sitting on the steps of a store where lotos bloomed in queer glass jars, noting the perfume but not caring to lift her head to learn whence it came. Their romping over, the cousins returned and led the way to the temple of Luxor, into whose shady recesses the scarlet-robed priests were bearing their boat-like shrine. Listlessly Mina followed. The dervishes gathered in a circle and swayed to and fro, wagging their heads. A white-robed priestess arose, and extending her wing-like sleeves, whirled around and around in utter surrender to the strange tinkling music and the jar of her own throbbing pulses. A sudden dizziness seized Mina, looking on. “I am faint; I will go out to the door until you come,” she whispered to Irma. Fritz, sitting near, caught the words.

“I will go too,” he whispered, officiously leaving his seat.

“Do let me alone for an instant,” exclaimed Mina, and pushing her way past him, hurried down the aisle. She saw, on pillar and wall, in colors which emphasized their grotesqueness, Osiris and Ammon-Ra, and Egyptian heroes, armed and splendid. She saw the mummy-cases arranged in rows, each upraised lid wrought into the image of a human form; each smiling, stolid face lit by the lamp swung under its bearded chin.

“Rameses II., who persecuted the Israelites,” read Mina, and bent forward curiously. Small, cruel eyes, showing beadlike, under half-closed lids; thin, dry lips, parted over broken yellow teeth, answered her innocent glance. He knew, this black-visaged king, what was in her heart, and mocked her tender quest, as he had mocked the zeal of Moses centuries ago. “Look at me,” he said, “and see what becomes of love and hope.”

With a smothered cry the frightened girl rushed from the place. Down the steps and through the crowded street she flew, past the camels and their laughing loads, the small, scudding donkeys and the noisy lads, out into the broad Plaisance, and on still, never stopping until she saw, within a stone’s throw, the square yellow and white gates which marked the limit of the Fair. This, then, was the end of the long, weary search! The taunting horror of the coffined face arose before her. “Life and Love and Hope are brief,” it said. “Only Death is long.”

‘‘Help me, oh, help me!” she moaned. “Pitying Mother of God, I shall go mad!”

“Mina, Mina,” rang out above the hum of many voices and the tread of many feet. “Mina, heart’s dearest, thou art come.”

Then all the crowded street and climbing towers went around before her eyes, and Mina fell, but knew in falling that her head was on Hermann’s breast and his arms were around her.

The procession moving up and down Midway stopped to stare, the waiters of the Captive Balloon came out like bees and swarmed around with offers of assistance, but to none would Sydow intrust his precious burden.

“Take her right into my room,” said Alma, and led the way herself.

“She is not dead! Mein Gott! she is not dead?” cried Sydow, so white was the fair round face upon the pillows.

“Nonsense; she will be all right in a minute,” answered Alma, slapping and pulling the limp form which Sydow had been treating as if it were china. Presently the childish blue eyes opened, and then, with mingled tears and smiles, in broken English and impetuous German, the lovers tried to tell each other in a moment’s time all that happened in the long five years.

The silver cross Mina devoutly accepted as a sign of consecration, and Sydow had not the heart to tell her upon what inappropriate scenes its light had shone.

After an hour had passed, they heard loud voices in the hall outside and Mina looked as if about to repeat her swoon.

“It is my uncle and Fritz, with Irma and Gertrude,” she said faintly.

Sydow started up as if to defy them, but Mina threw her arms around him. “No, no; not that again,” she begged. “See, the kind woman has gone to meet them.”

Through the partly opened door they saw Alma advance with more than her wonted dignity toward the excited quartet, who stood gesturing and declaiming in the center of the room. “Were you looking for someone?” they heard her ask.

“Yes,” roared Mina’s uncle, “and if I don’t get an answer soon from this impudent lot of lackeys I’ll break their heads.”

The waiters grinned.

“For whom were you looking?” asked Alma, quietly.

“For my niece, Mina Van Holst,” replied the other. “I know she is here, for people in the street saw her carried in.”

“Miss Van Holst is here,” replied Alma, “but she is with Baron Sydow, her betrothed husband, and they do not wish to be disturbed.”

“Baron Sydow! Ten thousand devils! Is Sydow here?” exclaimed Mina’s uncle. Fritz advanced a step or two and there was an angry glitter in his eyes.

“Yes; Baron Sydow is here with her, and they do not wish to be disturbed,” repeated Alma.

“Tell him Fritz Van Holst requires his presence,” said the cousin.

Alma stood haughtily before him. “I will tell him nothing,” she replied.

What he said then, under his breath, and in his own tongue, the watchful waiters did not know, but they read the meaning of the sneer upon his face and sprang forward, to a man, lining up before their mistress, exulting in the opportunity, new to them, of arraying themselves on the side of law and order, yet with the prospect of a fight.

Fritz cooled. There was a grewsome air of experience about the gang, which would lead a bolder man than he to deliberate. He said afterward that Irma and Gertrude held him back.

At any rate, the besieging party somehow deemed it advisable to leave the field, promising, however, to return tomorrow with re-enforcements.

The west end of Midway Plaisance, looking east, shows the Captive Balloon park on the left (north) side. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

But Baron Sydow threw his head back proudly. “I shall send her to Germany, to my own people,” he said, loftily, “and when I am through here, I will go there to be married.”

“Are you a fool?” stormed Alma. “Don’t you let her out of your sight. Hold her fast now that you have her, or you don’t deserve to be happy.”

“Aw right, aw right,” stammered Sydow; “jus’ as you say,” and away he went, walking on air.

The audience disappeared, with the exception of the waiters, who took advantage of a lull in business to talk over the affair.

“I know how it was, just as well as if I’d been there,” said Jake, when various conjectures were made as to “how Seedy got his head stove in.”

“Huh! you know too much,” said Tom, contemptuously.

“Shut up,” interposed Sam. “Less hear.”

“Well, it was like this,” said Jake: “Seedy comes up, bold as brass, and says, ‘Gi’ me my girl!’ and the old man, he says, ‘Yer can’t have her.’ Whiles they were a-talkin’, the two fricassees as were here to-day gets hold of Seedy’s two arms, and this young chap who thinks he’s so smart outs with a knife and cuts him so,” and Jake made a lunge forward in illustration.

“Sounds reasonable,” said Sam, nodding wisely; and Jake’s story of the fracas became the accepted version. As to the hero himself, he was bewildered by the changed attitude of the waiters. Sam took his hat and Tom his umbrella, and Jake yelled his order across the wooden counter in tones which could be heard half a mile away—that is, when the Dahomey warriors were not disporting on the roof opposite.

“Seedy’s a soft-spoken chap,” Jake would say when the gang rehearsed his romance among themselves. “But he’s a tarrier when he gits started.”

Sydow had to accept the absurd qualities in which they arrayed him, as he accepted the mantle of Mina’s loving idealization. The very tent and pavilion of the Captive Balloon were touched by the Ithuriel spear of Sydow’s romance. Allusions to the tender passion brightened all the songs. The air was full of sentiment.

“He’ll be the next,” said Alma, watching Professor Leigh unfold Miss Anderson’s umbrella and guide her carefully around a puddle. He was. He announced it the following day, with a gravity which hardly suited so joyous a theme.

“I have something of a confidential nature to disclose to you, Mrs. Read,” he said, solemnly. “I am engaged to Miss Letty Anderson.”

“Why, yes, of course,” said Alma—“I mean I am very glad. I hope you will be happy.”

“Thank you,” said Peter simply, and looked the boy he really was. “I shall always remember, and so will Miss Anderson, how kind you have been to us both.”

“It is nice to be young,” Alma said to herself, smiling, as he walked away. Alma was twenty-five.

A harsh voice broke in upon her reverie. “What are you doing here?” it asked.

She turned to confront the only man in the world who could shake her self-control. For an instant the steady gray eyes wavered and then they traveled swiftly over the unattractive figure before them, taking in the shabby frock coat, the battered hat, the dissipated face with its triumphant smile.

“What are you doing?” she asked.

“I am looking for my wife,’’ he answered with a leer. “She knows what I always want. Come, shell out.”

Without reply she led him to the little room which had witnessed such a different meeting a few days before.

“How much must you have?” she inquired, throwing back the trunk-lid.

“‘How much must I have?’” he repeated, mockingly. “Hullo! who’s that?”

The picture lay with its face turned upward, where she had placed it the morning after her talk with Sydow.

“Give it to me!” she demanded, with flashing eyes, as he caught it up for inspection.

“Who the devil is it, anyway?” He scowled at the beauty of the face.

“A physician in C——-, where you left me without a cent three years ago. I nursed a patient for him.”

“The devil you did!”

“Give it to me!” she cried, stretching out her hand.

“Give me the money first and I will.”

She flung the purse unopened at him. With a brutal laugh he tore the card across and tossed the halves into her lap, then went out and slammed the door.

* * * * *

To the cities built upon the shore of the great inland lakes there comes, sometimes, in mid-August, a chill as of winter. The rain falls in torrents and the wind rages like an uncaged beast. Such a chill, attended by such a storm, came to the city of the World’s Fair the night after Alma’s interview with her husband. The stately palaces of the Exposition leaked dismally, in spite of the efforts of workmen and guards. On Midway, many a flimsy structure went down before the gale. The pavilion of the Captive Balloon looked like the drenched deck of an ocean steamer, the central office serving for a pilot-house. Over its wet, slippery floors, the waiters dragged chairs and tables to a place of safety.

About the shelterless balloon the rain and wind whirled with redoubled fury. “Varnished silk and hempen twine—bah!” said the rain. “Wooden clappers and bags of sand—pouf!” said the wind; and they dashed against it, pulling and pushing, till a cable snapped. Then how they pounded the helpless thing over the ground.

“Gone up, that’s a fact!” said Ives, examining the wreck by the morning’s sunshine.

“Gone down, you mean,” said Alma with a faint smile.

“And there’s that blamed concession,” continued the aeronaut, gnawing his mustache. “We can’t stop; we’ll have to make the restaurant and the stage pay as well as we can. You’ll have to keep right on, Mrs. Read.”

“Oh, yes,” replied Alma, gravely; “I’ll have to keep right on.”