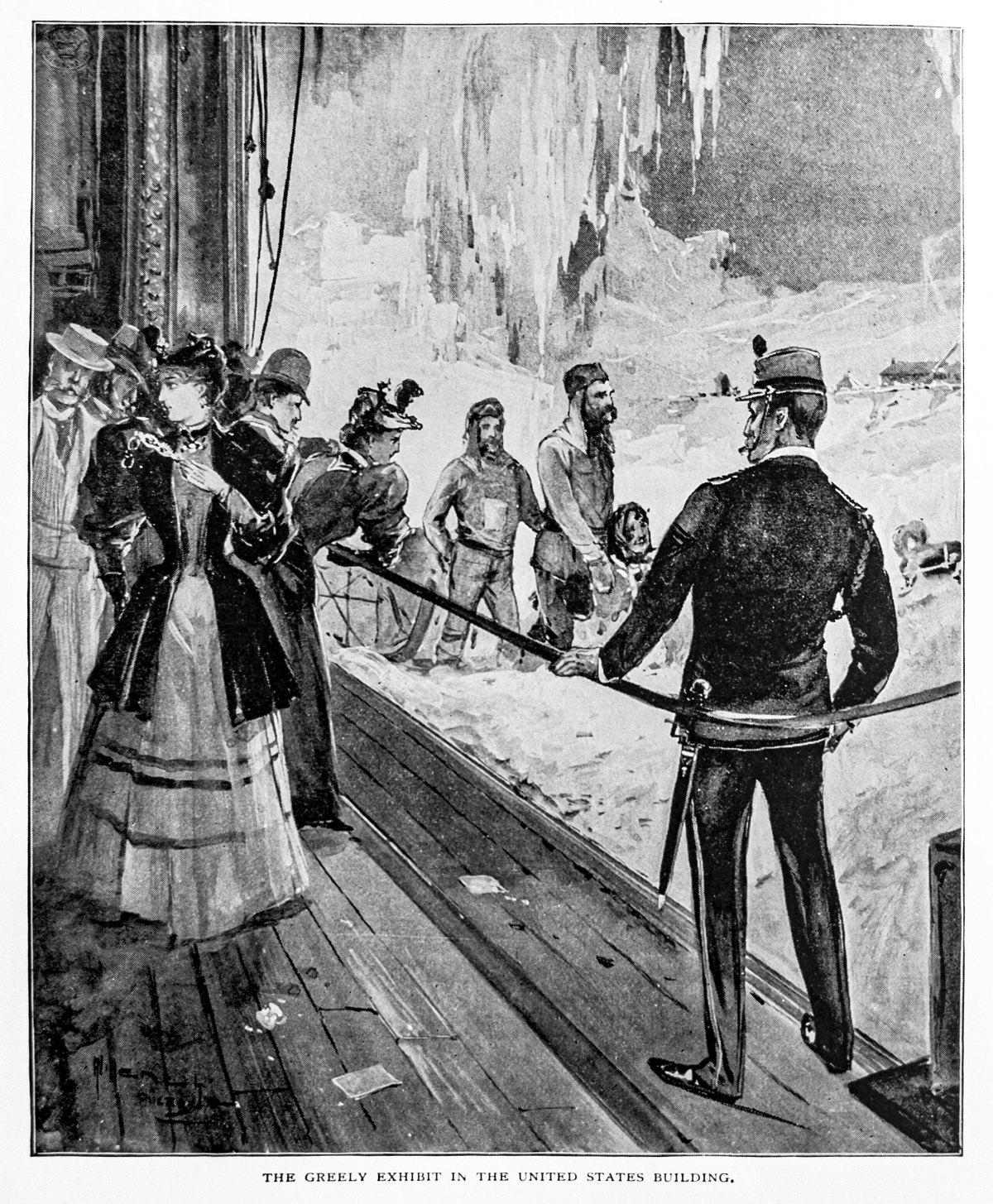

Crowds gather at the 1893 World’s Fair to see a panorama depicting the Greely Expedition to the North Pole. [Image from the Illustrated American World’s Fair Special Issue, 1893.]

An exhibit in the United States Government Building at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition honored Brainard, Lockwood, and Greely. Installed by the Signal Service Bureau in the War Department section of the building, southeast the rotunda, an arctic tableau recreated a scene from 1892 of Greely greeting Lockwood and Brainard as they returned from their expedition that had brought them closer to the North Pole than any previous Arctic explorers. The Signal Corps was headed, interestingly enough, by Adolphus Greely, who has been appointed to the post in 1887 by President Cleveland. [Levy 338]

A floorplan of the War Department section of the U.S. Government Building showing the location of the Greely Expedition Arctic tableau. [Image from Plans and Diagrams of All Exhibit Buildings in the World’s Columbian Exposition. Conkey, 1893.]

The most striking of all the displays

The Arctic panorama conveyed to fairgoers this important achievement of United States Army in the field of exploration. One World’s Fair chronicle described the theatrical medium this way:

“This white scene was perhaps the most striking of all the displays in the wonderful museum which the United States opened at the World’s Fair. The exhibit was built in the manner made familiar to residents of cities through what are called cycloramas, where lay figures and actual properties take stated positions before the painting, and become an inseparable portion of the scene.” [Dream City] Positioned in the foreground of a great icy field were life-size wax figures of the Army officers dressed in their heavy Arctic garments. Greely stands at the right shaking hands with Lockwood while Brainard stands behind him further to the left. Lieutenant Greely is accompanied by an orderly. An Inuit guide squats behind the three officers, busily attending to his dogs.

The scale of the panoramic display inside the U. S. Government building is apparent in this photograph of the Greely Expedition tableau. [Image from Buel, J. W. The Magic City. Historical Publishing Company, 1894.]

On the sled was a small United States flag, made by Mrs. Greely, that the explorers had carried to the point “Farthest North.” Two signs placed in the scene provided visitors with a brief history of the momentous event of the Greeley expedition.

A photograph of the Greeley Expedition tableau used in Kilburn stereoview card 7994, showing the dogs, sledge, and American flag. [Images from the New York Public Library.]

A photograph of the Greeley Expedition tableau used in Kilburn stereoview card 7993, showing details of the snow scene. [Images from the New York Public Library.]

A sublimely thrilling incident in Arctic exploration

Serving as a backdrop was “a large painting showing the awesome cape as it extends into the sea, the northernmost discovered land.” [Dream City] The base camp at Fort Conger can be seen in the distance, and the members of the Arctic expedition “standing on the land in the background, waving their hats with joy, add a bit of spirit to the scene.” [“Uncle Sam’s Big Show”] The space between the figures in the foreground and the immense canvas at the rear was filled with an icy Arctic landscape. Plaster snow drifts and icebergs created “a realistic Arctic scene with its bleak desolation of tumultuous ice packs and boundless fields of snow glaring under a sun that dazzles but does not heat.”[Magic City]

Tableau of Lieutenant Greely greeting Lieutenant Lockwood and Sergeant Brainard on their return from the “Farthest North.” Notice Fort Conger with cheering members of the expedition on the backdrop painting. [Image from Harper’s Weekly Nov. 4, 1893.]

Scenic painter Albert Operti also produced this portrait of the explorer David L. Brainard for Hassan Cork Tip Cigarettes. [Image from the Brainard Collection of Arctic Exploration of the National Archives.]

No one can fail to be impressed

Historians White and Igleheart described the Arctic tableau as “one of the most entertaining [exhibits] of all in the building… The scene is so perfectly constructed that no one can fail to be impressed by it, and to receive a better idea than ever before of the exact circumstances and conditions surrounding Arctic exploration.”[White 468] Another historian noted that “everything in the picture is lifelike.” [Cameron 482]

“The figures of Greely, Lockwood and Brainard are well executed,” wrote one newspaper reporter, “and the animals are exceedingly life-like, being the stuffed skins of Esquimaux dogs. The imitation of ice all around is realistic enough to deceive many visitors.” [“Uncle Sam’s Big Show”]

“By the aid of mirrors and artificial light,” wrote one news report, “an effect is promised which will exceed all previous attempts at wax portraiture, and the spectator will with difficulty persuade himself that he does not look upon a living group and an Arctic Sea.” [“From Chicago”]

One young girl visiting the fair described her encounter with the Arctic scene:

“We next visited the Government Building, where we saw life-size figures of the Greely party, as they appeared while hunting the North pole. You could scarcely tell they were not real. Two men were shaking hands and one dog lay dead at their feet and others were standing around. This is represented in front of a mountain of snow. The icicles are hanging all around.” [“Seen by a Young Girl”] The entire display presented a “vivid reproduction of Arctic scenery” [Truman 399] and “an artistic centrepiece showing that the Stars and Stripes have been further north than the flag of any other country …” [Northrop 345]

A newspaper illustration depicting the “return from Farthest North” tableau modifies the scene by giving Lieut. Greely a rather long beard, repositioning the dogs, and planting a large American flag into the Arctic background. [IMAGE from a news service story “Uncle Sam’s Big Show” that ran in the Buffalo (NY) Evening News, June 10, 1893.]

A beautiful combination of model and painting

The 1893 World’s Fair offered several panoramic attractions to entertain and educate visitors, including a Volcano of Kilauea Cyclorama and Panorama of Bernese Alps on the Midway Plaisance. The Arctic tableau sponsored by the U.S. War Department provided “a beautiful combination of model and painting that exhibited such an excellent reproduction of this memorable incident, that it drew immense crowds, who thronged in front of it almost continually, and whose interest and admiration was unbounded.” [Magic City]

The Boston Globe reported in May, when attendance at the Exposition was lagging, that “the centre of attraction [in the U.S. Government Building] for some reason seemed to be the icy scene …” [“Big Crowds”] As the weather got hotter, fairgoers kept coming for the cool view. “This Farthest North panorama is always surrounded by large crowds of visitors,” reported a syndicated story in June. [“Uncle Sam’s Big Show”]

“While this scene gives a glimpse of the romance and triumph of the Arctic field,” wrote one journalist, “but a few feet away is a collection of articles which speak eloquently of the suffering and death which sometimes follow effort in the frozen north.” [“Uncle Sam’s Big Show”]

Images of the Greely Expedition paintings and tableau. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

The most remarkable episode of its kind in history

Of the original twenty-five men in the Greely Arctic Expedition, only seven survived the brutal conditions to return home. They were rescued in July of 1884, two years after their expected supply ship failed to reach them with essential provisions. (For more on the tragedy of this expedition, see “The Greely Expedition“, Season 23 Episode 5 of The American Experience on PBS or “Abandoned in the Arctic on Vimeo” on Vimeo.)

Next to the panorama was exhibited a framed painting detailing the rescue scene, “probably the most remarkable episode of its kind in history,” according to The Dream City. “As may be seen, the few survivors are within hut a few hours of death by starvation, after trials and privations which were carefully suppressed from the public reports.” Other paintings of Arctic scenes by famous artists and a large collection of enlarged photographs and portraits of famous Arctic explorers also accompanied the tableau.

A painting of the rescue of the Greely Expedition survivors. [Image from The Dream City. A Portfolio of Photographic Views of the World’s Columbian Exposition. N. D. Thompson, 1893.]

Both Greely or Brainerd continued to serve in the U.S. Army in 1893, and it does not appear that either of them visited the great fair in Chicago to see their representations on display.

A portrait of Lieutenant Adolphus W. Greely in 1893. [Image from the Reading (PA) Times Sept. 16, 1893.]

A portrait of Sergeant David L. Brainard in 1898. [Image from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer Jan. 6, 1898.]

SOURCES

Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.

“Big Crowds at the Fair” Boston Globe May 14, 1893, p. 2.

Buel, J. W. The Magic City, A Massive Portfolio of Original Photographic Views of the Great World’s Fair and Its Treasures of Art, Including a Vivid Representation of the Famous Midway Plaisance. Historical Publishing Company, 1894.

Campbell, James B. Campbell’s Illustrated History of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Volume II. M. Juul & Co., 1894.

Cameron, William E. The World’s Fair Being a Pictorial History of the Columbian Exposition. P.D. Farrell, 1893.

The Dream City. A Portfolio of Photographic Views of the World’s Columbian Exposition. N. D. Thompson, 1893.

“From Chicago” The Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu, HI) March 4, 1893, p. 5.

Hamilton, W. E. The Time-Saver. W. E. Hamilton, 1893.

Levy, Buddy Labyrinth of Ice: The Triumphant and Tragic Greely Polar Expedition. St. Martin’s Press, 2019.

Northrop, Henry Davenport The World’s Fair as Seen in One Hundred Days. Ariel Book Co., 1893.

Official Catalogue of Exhibits, World’s Columbian Exposition U. S. Government Building. W. B. Conkey, 1893.

Plans and Diagrams of All Exhibit Buildings in the World’s Columbian Exposition. Conkey, 1893.

“Seen by a Young Girl” The Weekly Clarion Ledger (Jackson, MS) Sept. 14, 1893, p. 1.

Truman, Benjamin Cummings History of the World’s Fair. Mammoth, 1893.

“Uncle Sam’s Big Show” Buffalo (NY) Evening News June 10, 1893, p. 7.

White, Trumbull; Igleheart, William World’s Columbian Exposition Chicago, 1893. J. W. Ziegler, 1893.