Halcyon Days in the Dream City

by Mrs. D. C. Taylor

Continued from Part 10

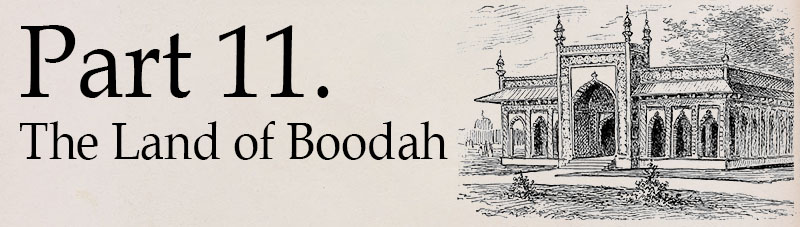

A low curved roofed, wide eaved temple, built of foreign woods covered with intricate carving, with deep lace-arched balconies, and blind walls, windowless and dark.[1]

The East India Government Building at the 1893 World’s Fair. [Image from The Graphic History of the Fair. Graphic Co., 1894.]

Myriads of little elephants, from two inches to two feet in height, fashioned of porcelain, ivory, ebony, brass and woods, stand about everywhere; and still more numerous, in the same materials, gazing up at us from low pedestals upon the floor, looking down upon us from the gallery, on every side we turn are expressionless cross-legged images of Boodha. Truly he is a God! not the supreme “I AM,” but one of the Gods of whom there are as many as there are men to create them. The eternal calm of Boodha is an eternal void, NOT the divine calm of life at its fullest fruition.

Carvings inside the East India Building. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

Here stands an alabaster model of “The Taj,” inexpressibly beautiful in its white fineness, with its mournful breathing of human grief, sighing down through long centuries of time, that love only, is eternal. Little bells whose mellow sweetness of tone touches the ear with a note of sadness, hang pendant from shrine and idol; stacks and piles of tea trays and the fragrance of tea upon the air, let us descend and take a cup of tea.

The exhibit of S. J. Tellery and Company in the East India Building. [Image from Campbell, James B. Campbell’s Illustrated History of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Volume II. M. Juul & Co., 1894.]

There we find a space enclosed by screens and crowded with small round tables surrounded by chairs. The place is appetizing with the odor of tea, and a huge bright metal urn is hissing and steaming upon a high counter. Threading our way through a dense tangle of human and chair legs, we seat ourselves at one of the tables, .and wait until there comes up another red robed “prince,” and places upon the table two dainty red and white cups and saucers, a generous pot of cream, a bowl of lump sugar, and a little black and gold tea-pot, full of tea hot and strong. How delicious it tastes to our thirsty palates. The two cups empty the little tea-pot, but another immediately replaces it full to the brim, and we are welcome to its cheer without money or price.

Dignified forms move quietly on slippered feet from table to table, fetching, carrying without haste or dallying, politely attentive to everyone, the perfection of service, and as we pass out with murmured thanks, each man bends his head in low, but stately parting “salaam.” For six months this generous hospitality was extended to the world at large, and our thirsty lips returned more than once to this perennial fountain of Oriental nectar.

And so, India goodbye! and we have not even glanced at your far famed shawls! our souls yearned for them but our impecunious purses passed them by. Good-bye! Land where Buddha sits entranced, while his dreaming followers pass proudly through squalor and toil to their rest in the vast realm of “Nirvana.”

Continued in Part 12

NOTES

[1] Standing just north of the Fisheries building, the East India Building also was designed by Henry Ives Cobb with Director of Color William Prettyman in charge of its decoration. The building impressed visitors with its gold-canopied arched entrance surmounted by minarets.