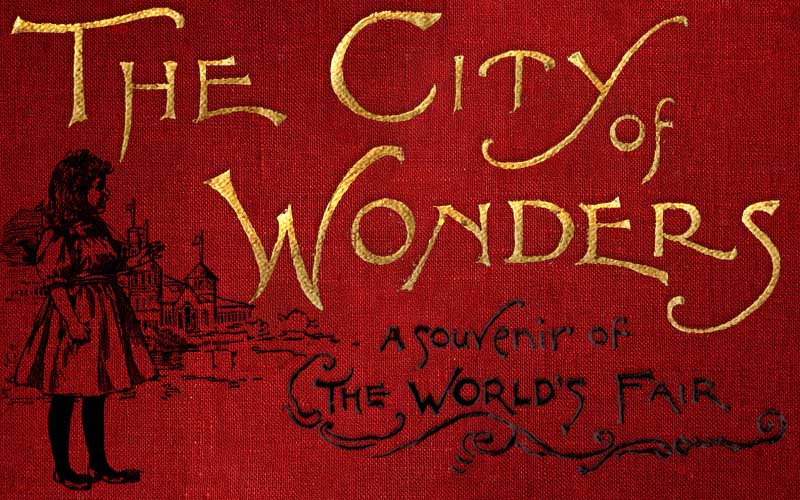

THE CITY OF WONDERS

A Souvenir of the World’s Fair.

BY

MARY CATHERINE CROWLEY

CHAPTER 7. A VARIETY OF ENTERTAINMENT

[For other installments of our serialization of The City of Wonders (1894), see the Table of Contents]

The United States Government Building, looking eastward from Wooded Island at the 1893 World’s Fair. [Image from Vistas of the Fair in Color. A Portfolio of Familiar Views of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Poole Bros., 1894.]

Fair by way of the Lake. Arrived at the wharf, he secured tickets via the fine new steamer, Christopher Columbus. As they went on board, the young people observed at once that it was unlike any boat they had ever seen.

The whaleback steamer Christopher Columbus transported fair visitors between downtown Chicago and Jackson Park. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

They walked about, delighted with the handsome appointments of the immense open cabin; the girls glancing shyly into the long mirrors every now and then, not so much to catch a glimpse of their own faces, as to watch the ever-varying throng of promenaders, or to admire the deep reflections of the long vistas of rich carpetings, polished tables, and luxurious arm-chairs and divans.

Uncle Jack, however, hurried them out on deck, and obtained places for them in the bow of the boat. The great vessel had already started and was steaming up the Lake with a kind of majesty, “as if proud of the name it bore,” Aleck declared. The two girls grew enthusiastic as the broad expanse of waters seemed to widen before them on three sides, bounded only by the distant horizon; while on the fourth extended the proud city, representing many miles of towering structures, of splendor and prosperity.

A half hour’s delightful sail, and then, as if evolved from the fleecy clouds floating low in the azure sky, there appeared along the shore, one after another, the ethereal, ideally beautiful buildings of the City of Wonders.

“How lovely they look across the blue sparkling waters!” exclaimed Nora.

“It seems like the city of a vision” murmured Ellen, who was fond of poetry.

“Or a day-dream of ancient Greece in the era of her glory,” added Uncle Jack.

Aleck said nothing. He was not given to poetic musings and was more than half convinced that the ancient Greeks had lived only to make trouble for the average school-boy destined to wrestle with a college course.

He simply admired the scene for what it was and probably appreciated it as much as any of the party.

The moving sidewalk on the Pier. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“Suppose we go up into the grounds on the moving sidewalk?”[1]

“The what?” asked Nora, doubting if she had heard aright.

Mr. Barrett repeated the words with a smile, adding:

“There are many novel ways of getting about at the Exposition, you perceive.”

“In fairy tales I have read of a magical carpet, upon which one had only to place one’s self to be transported wherever one wished,” said Ellen: “But this must be even more convenient. How nice, instead of trudging along on the sidewalk, to just stand still, and let the sidewalk do the travelling!”

Passing through the entrance gate, they crossed the pier to the point where this singular promenade began and were admitted to a platform similar to that of a railway station, but which continued the entire length of the route. Extending along beside this was a plank walk, with seats ranged across it, like those of an open street-car.

“You see, you will not even have to stand. Take places all of you,” said Uncle Jack.

Now the mysterious sidewalk began to move. The sensation was as if the ground were slowly slipping away from beneath their feet; and yet they were themselves carried along with it. They stood up to try what it would then be like, and felt as if they were running, though they had not put one foot before the other. In this manner, a distance of perhaps half a mile was traversed.

Then a man shouted that they had better get off, unless they wanted to go back again, so they stepped out on the stationary platform and watched the sidewalk glide past them in the opposite direction.

“Is it not extraordinary?” cried Nora.

“Fudge! There is nothing so very wonderful about it, after all,” rejoined Aleck, who, having leaped down the steps, had found a broken board at the side of the platform, and was peering underneath. “Your moving sidewalk, which you are staring at as if it were enchanted, is merely an electric railway train, with the wheels and running gear concealed. See, they are all under here.”

The girls peeped in and found this to be the fact.

Uncle Jack laughed.

“So you have solved the mystery?” said he. “Let us commemorate the fact by having some ice cream soda.”

The Casino building, designed by Charles B. Atwood. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

The “Big Tree” exhibit from California in the U.S. Government Building. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

In the Massachusetts booth Aleck was attracted by a clumsy copper watch, that once belonged to Captain Miles Standish. Here, too, they saw pieces of colonial money, swords worn at the battle of Bunker Hill, quaint silver porringers and tankards, a long tongs-like pipe-lighter found in a colonist’s house, and a salt-cellar owned by Mary Chilton, the first woman who stepped on Plymouth Rock at the landing of the pilgrims of the Mayflower. The most interesting of these souvenirs, however, was a bottle containing a few grains of tea said to have been found in the boots of one of the members of the Boston Tea-Party on the night of December 16, 1775, after he returned home from that historic entertainment.

“See among what Rhode Island has to show,” called Ellen, “the inkstand from which the Declaration of Independence was signed, a compass that belonged to Roger Williams, a bit of the Charter Oak, an Indian deed of land, and an invitation to dinner from General Washington.”

“Maryland displays many keepsakes, including these grants of territory bearing the seal of Lord Baltimore,” said Mr. Barrett. “But the most precious, I think, is this old sheet of paper, the original manuscript of our noble national anthem, ‘The Star-Spangled Banner,’ with the signature of the author, Francis Scott Key.”

In the Pennsylvania exhibit were mementos of Franklin and other illustrious men of the Continental Congress. Of the articles in this department, however, the object which especially caught the attention of the girls was a little old doll, once considered handsome no doubt, but now very shabby indeed.

“Oh, look, Ellen!” cried Nora. “This was a present from General Lafayette to a little girl named Hannah–I can’t exactly make out the last name. He sent to Paris for it. Just think! Even if she lived to be an old lady, she must be dead ever so long; and yet here is the doll she used to play with. I suppose, considering that it is more than a hundred years old, it is not so bad; but what a contrast to the lovely French dolls we saw in the Manufactures’ Building! Look at the queer plaster head, with the paint half rubbed off the face; and the limp kid arms and legs. There is not a joint in its body, poor thing! The clothes are faded and spoiled now, but they must have seemed very fine to Hannah.”

The central rotunda of the U.S. Government Building. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“Actually, here is the commission of George Washington as commander-in -chief of the American army! Think of that!” exclaimed Aleck.

“Yes,” answered Uncle Jack: “It is the veritable document which, humanly speaking, gave into his hands the destinies of the colonies, and which he resigned to the commissioners at Annapolis at the close of the Revolution. Above it hangs his sword.”

Nora and Ellen viewed, with housewifely pleasure, a service of pewter upon which the General’s dinner was daily served in camp, and an old ledger used in settling up the accounts of Mount Vernon. There were several volumes of Washington’s diaries, too.

“Here is one of the greatest curiosities of the Exposition,” called Uncle Jack, from a case farther along.

When they came up, he pointed out a wampum belt made by the Iroquois Indians of New York to commemorate the confederation of the Five Nations, believed to have taken place before the discovery of America.

“Now,” he continued, “I am going to show you one of the two pre-eminently great historic treasures of our country.”

He led them on, and presently paused before a large framed document on the wall, encircled by the folds of the Stars and Stripes, and guarded by two soldiers with loaded muskets.

“This,” said he, “is the original Declaration of Independence.”

A thrill of patriotism, like an electric current, seemed to pass over our young friends as they gazed upon the parchment.

“Those are the words written by Thomas Jefferson as the expression of the sentiments of the Continental Congress, and pledged to by the patriots whose names are signed below,” he went on: “The words which threw down the gauntlet of defiance to Great Britain, and which, sealed by the blood of heroes, made this the land of liberty and the greatest nation of the earth. Picture to yourselves that solemn signing, when these brave men and true, risking their all, took upon themselves personally the consequences and responsibility of their act in declaring these United States free and independent. It was no high-sounding, empty phrase, that pledging of their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor; for they were all men of wealth and eminence, who bad much to lose. Should the Revolution fail, their names would be execrated, their possessions forfeited to the Crown, while they themselves would be condemned to the ignominious death of traitors.”

As the girls and Aleck scanned the signatures, Mr. Barrett speculated upon the thoughts and emotions of the patriots as they signed the document, which was to lead to such glorious results.

“Naturally, the bold handsome signature of John Hancock first strikes the eye,” he said. “How well it expresses the determination, the polished manners, and the moral courage of the President of the Continental Congress!”

“The Signers all seem to have been better writers than you would find among the same number of men nowadays, I’ll wager,” said Aleck. “To judge from the curves and flourishes, they appear to have been pretty cool about the matter too; all but this shaky scrawl of Stephen Hopkins, which makes one think he must have been terribly frightened.”

“The good man’s hand trembled, no doubt; but it was not from fear,” said Uncle Jack. “He was grievously afflicted with the palsy but was one of the staunchest of the patriots. Then, here are the signatures of Samuel Adams, who, some time before, had returned the message to the British Governor: ‘No personal considerations would induce me to abandon the cause of the colonists’; John Adams, whom Jefferson called the pillar of the Declaration in the Congress; of Benjamin Franklin; and of Jefferson himself, more hastily written perhaps, dashed off with his usual enthusiasm, but revealing something of the strength and firmness of his character; Richard Henry Lee, who first brought before the Congress the motion for the proclamation of Independence; Charles Carroll of Carrollton whose graceful penmanship bespeaks the man of polite learning; courteous, dignified, punctilious in regard to all the observances of the formal society of the period, as well as prompt, energetic and generous as a statesman. And so on through the long list of fifty-six glorious names.”

“You spoke of two especially important historic documents, Uncle Jack,” resumed Aleck. “I suppose the other is the original draft of the Constitution of the United States. Is that to be seen here at the World’s Fair too?”

“No,” was the reply. “Unfortunately for us, but perhaps wisely, it was not considered advisable to allow this priceless manuscript to pass out of the keeping of the Department of State at Washington.”

In the exhibit of the latter department, Mr. Barrett found much to interest him among the famous state papers, which are a part of the history of the country.

“Look!” he continued. “This is the Treaty of Peace with Great Britain, which concluded the war of the Revolution. Notice, it begins with the reverent words: ‘In the Name of the Most Holy and Undivided Trinity.’ And here is the Treaty of Friendship and Alliance, which gave to the United States the aid of France during that great struggle.”

Now our friends passed on to the War Department, where Uncle Jack and Aleck examined and discussed the various kinds of rifles and cannon, stopping frequently to talk to the soldiers who were there to explain them.

It was a pleasant diversion for Nora and Ellen when they came unexpectedly upon a kind of panorama of the frozen North, and a number of souvenirs of Sir John Franklin, Kane, and other explorers, who penetrated into that perpetually ice-bound zone. Nora was almost as enthusiastic as her brother when Mr. Barrett pointed out two faded standards, which looked as if they had seen much service, saying:

“This one is the first flag raised in the Arctic regions. It belonged to the Grinnell Expedition. The other was the banner of Lieutenant Greeley’s party, and was planted on the spot nearest to the north pole which the foot of civilized man, or perhaps of any human creature, ever trod.”

The Model Post Office inside the U.S. Government Building. [Image from Johnson, Rossiter A History of the World’s Columbian Exposition Volume 3 – Exhibits. D. Appleton and Co., 1897.]

The exhibit of the Smithsonian Institute in the U. S. Government Building. [Image from Shepp, James W.; Shepp, Daniel B. Shepp’s World’s Fair Photographed. Globe Bible Publishing, 1893.]

“I am afraid we cannot delay here any longer; for we seem to be like the Wandering Jew, forever condemned to keep moving on.”

The battleship U.S.S. Illinois exhibit on the lake shore. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“This is the most striking object of the Naval exhibit,” observed Mr. Barrett. “It is built of brick and mortar, and is stationary, because the water at the wharf is too shallow for a real ship of such great size; but as far as dimensions and equipment are concerned, it is an exact counterpart of one of Uncle Sam’s splendid new steel cruisers. The original, though a beautiful object, in time of war would prove a powerful protector of our ports and defender of our national honor.”

“H’m,” said a sailor-soldier, who conducted them through the vessel. “There would be a small chance for any city that happened to be shelled by these guns.”

Then he went on talking about bombs, torpedoes, etc., till Ellen thought he would never stop.

[The Kendricks fourth day at the Fair continues in Chapter 8 of The City of Wonders, with visits to several state buildings, the Palace of Fine Arts, and other exhibition halls.]

NOTES

[1] “Suppose we go up into the grounds on the moving sidewalk?” The moving sidewalk did not open until early June and was immediately plagued with mechanical problems but seemed to be running steadily until early July. By the time the Exposition closed, it reportedly had carried 997,785 people.