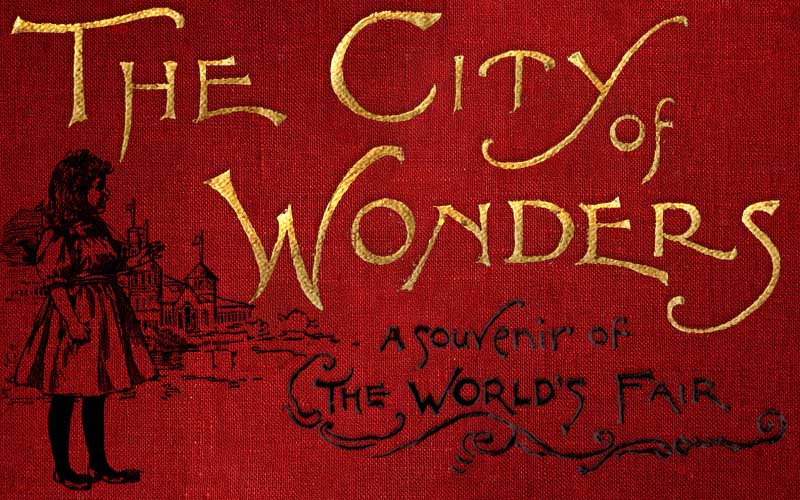

THE CITY OF WONDERS

A Souvenir of the World’s Fair.

BY

MARY CATHERINE CROWLEY

CHAPTER 6. STRANGEST OF ALL

[For other installments of our serialization of The City of Wonders (1894), see the Table of Contents]

The Electricity Building of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition at night. [Image from Graham, Charles S. The World’s Fair in Water Colors. Mast, Crowell & Kirkpatrick, 1893.]

“The display here is the most novel and interesting in the Exposition,” said Mr. Barrett. “But the exhibit of the progress of electric science extends throughout the World’s Fair, supplying the power for much of the machinery, as well as the illumination of this White City of Wonders, and the beautiful colored lights and fountains which make it a perfect fairyland in the evening.”

The Edison Tower of Light in the General Electric exhibit in the Electricity Building. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“It is like a pillar built with millions of jewels,” said Nora.

“Yes,” agreed her uncle; “and the colors are arranged in such a way that they may be flashed in harmony with the strains of music.”

It was interesting also to see the electric locomotive, which will be apt in time to supersede the steam engine; and to watch the processes of electroplating, forging, welding and stamping metals.

A guard directed them to the special Edison exhibit, situated in the spacious gallery, away from the noise and confusion of the main floor. Climbing the stairs, they came upon it at once.

Thomas Edison’s phonograph exhibit in the Electricity Building. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

He led them to a queer instrument which they might have mistaken for some kind of sewing-machine or typewriter, but that hanging around it were several small rubber tubes divided at the end, so that one point might be placed in each ear of the listener. Our friends each took up a tube and adjusted it according to directions; a cylinder was placed in position, and the phonograph set in motion, and presently they heard the rich tones of a master of elocution declaiming one of Longfellow’s poems:

“I shot an arrow into the air.”[1] “Gracious me, it seems as if a man were shouting right into my ear!” cried Nora.

As they all complained not, as one might suppose, that they could not hear, but that the voice was too loud, the attendant advised them to hold the tubes a little farther away.

Next they were favored with a song by a popular professional singer.

“Isn’t it Mr. C—-‘s voice to perfection, Nora?” said Ellen. “Don’t you remember, we heard him at the Orphans’ Benefit Concert last winter?”

This piece was followed by a brilliant performance of instrumental music.

“It is hard to believe that some one is not playing the piano right near here.” exclaimed Aleck.

“What a clever little messenger the phonograph can be too!” suggested Uncle Jack. “A traveler instead of writing to his friends at home, can box up a cylinder full of tourist’s gossip, and send it by express. A merchant may dictate his letters into a phonograph after office hours, and the next day his secretary will be able to write them off without interrupting him. With a phonograph one might live alone and still enjoy the conversation of one’s friends, lectures, and the best parlor music. And then, it would be only necessary to stop the machinery to insure perfect quiet when one wanted it.”

“One would think the phonograph was invented especially for old bachelors,” whispered Nora to her sister with a laugh.

Uncovering a cylinder that had been carefully wrapped in cotton-wool, the attendant put it in place, and now from the wonderful machine there rang out the clear, decisive tones of a public speech.

“Capital!” cried Uncle Jack. “It is President Cleveland‘s voice, and the words are those of his inaugural address. I am almost constrained to believe that I am again in Washington at the Inauguration.”

After this, the young people listened to a German lesson from the phonograph.

Exhibits inside the Electricity Building. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“Oh, yes!” interrupted Aleck. “I have read of it. That makes a shadow talk does it not?”

“It is a contrivance by which every gesture of a speaker may be photographed at the same time that every word he utters is recorded in a phonograph,” was the reply. “When the picture is thrown upon a screen, and the talking-machine started, the illusion produced is that the shadow is speaking. Mr. Edison is said to have perfected this curious invention for his own amusement, as a relief from more serious work.”

By turns they looked into the telescope of the kinetograph. There, sure enough, was a shadow-man, who nodded and smiled, and began to talk sociably, asking many amusing questions; then he recited something, and finally sang a popular song. Pleasing as this performance was, the effect was rather startling, and the girls and Aleck could hardly rid themselves of the idea that there was some magic about it.

“It beats all the fairy tales I ever heard,” declared the latter.

“No wonder Edison is called a wizard,” remarked Ellen.

Elisha Gray’s Telautograph, a device invented to transmit handwriting over electrical telegraph signals. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“Experiments show that this can be done as readily at a greater distance,” he said. “It is expected that when this invention is generally introduced, one will be able to send a letter by telegraph in one’s own handwriting.”

“For instance, Miss,” he added, turning to Ellen, “suppose you wanted to write to your mother from the World’s Fair, and there was telautographic connection with your home, just as so many families have a household telephone nowadays. All you would have to do would be to take your place at this desk and write a letter. When you had finished, your mother, going into the library at home, would find the letter neatly copied upon the tablet on her writing table.”

“Astonishing as this seems,” interposed Mr. Barrett, “it is not an impossibility. It would not be, after all, so wonderful as the telephone, which was at first regarded as a curious toy, but which we now use as a matter of course, almost for-getting. that it is at all remarkable.”

“Why, when the telautograph becomes common there will be an end to the postman,” said Nora.

“I presume the inventor anticipates that it will lighten the mails somewhat,” conceded Mr. Barrett, smiling: “But, however such matters may be arranged in the future, I hardly think Uncle Sam’s letter-carrying business will be seriously interfered with for some time to come.”

The model kitchen powered by electricity. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

The girls were delighted with this little domestic corner. Here was a range supplied with heat from the electric wires of the incandescent lamps used for lighting the room. Through the glass door of the oven, (a novelty in itself,) they saw a joint of meat roasting, and on top of the stove the vegetables and a plum-pudding were boiling.

“When electricity takes charge of our households,” pursued Mr. Barrett, “every family will keep a footman. We shall only have to touch an electric button in the parlor wall, and presto !–a special little elf will throw open the door to our visitors. It also plays the rolê of policeman. See these clever devices for the detection of intruders or light-fingered persons. When a burglar or sneak thief attempts to take a coat from its hook in the hall, an electric current sets an alarm bell ringing; this other neat contrivance is designed to protect one’s purse from pickpockets in the same way.”

The exterior of the Mines and Mining Building, designed by architect Solon S. Beman of Chicago. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“Look at the nugget of gold in this case,” called Aleck. “It is as big as a man’s fist.”

“Here is a bit of ore from the celebrated silver room of a mine in New Mexico, in which a space the size of a small apartment produced $500,000 worth of the precious metal,” observed Uncle Jack. “And now we come to Montana’s famous statue.”

The solid silver statue of Justice by Richard Henry Park in the Montana exhibit of the Mines and Mining Building. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“It represents Justice,” continued Mr. Barrett. “See, in one hand she holds a sword aloft, and in the other the scales. Though portrayed as blind in olden times, she now has her eyes open; for Justice indeed needs to be very wide awake nowadays. The value of the statue is, of course, enormous; but, apart from its intrinsic worth, there is something poetic to me in employing this noble metal for the personification of the civil virtue which is the most precious of man’s possessions, the unsullied guardian of his rights.”

A miniature coal mine, and models showing the various methods of mining, occupied the attention of Uncle Jack and Aleck for some time. Then the former, perceiving that the girls were tired, called a halt for luncheon, and afterward engaged rolling chairs for them. They now enjoyed the novelty of being wheeled through the Agricultural Building, while he and Aleck, still preferring to go afoot, walked beside them.

The Agricultural Building, designed by McKim, Mead & White of New York. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“Yes, the foreign Governments and the States of the Union have housed their exhibits in beautiful little edifices, which tell their own story,” returned Uncle Jack. “Most of these were constructed in their native climes, of the wood or other products of the state or country and shipped to Chicago in sections. That charming little Greek palace opposite belongs to Nebraska. Its graceful colonnades look like columns of colored marbles, but as we draw nearer you will observe that they are glass tubes filled with seeds of grain.”

The Nebraska Pavilion made of corn. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“Here is a pavilion formed entirely of sheaves of rye or barley,” said Ellen.

“Oh, look at the people on top of it! “ chimed in Aleck.

There, sure enough, were figures representing a family–father, mother, and two children, a boy and a girl, –dressed in complete suits of the long grain, with hats to match.

Germany’s Stollwerk Brothers exhibits a temple made out of thirty thousand pounds of chocolate and cocoa butter that enshrined a statue of Germania, ten feet tall in solid chocolate. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“Scotch granite,” answered Nora.

“No, my dear, it is built entirely of chocolate.”

“Of chocolate!” repeated Aleck, smacking his lips. “I should think everybody who passes would want to break off a piece.”

“Well, there are 30,000 pounds of the toothsome material here,” replied his uncle, laughing. “It is the exhibit of a manufactory in Germany. That great statue of Germania under the dome is hewn from a solid block of chocolate weighing about 3,000 pounds. Let me propose a sum in arithmetic to you. If one thousand boys and girls were each allowed one pound and two-thirds of seven-eighths of a pound a day, how many days would it take them to dispose of the 33,000 pounds?”[3]

“Pshaw, fractions! And it is vacation!” protested Nora. “No, Uncle Jack, I would not bother with your example for the whole pagoda. But if the men who erected it want to know the time in which it could be made away with, they had better break it down with a sledgehammer and invite the boys and girls to help themselves.”

[The Kendricks return to the fairgrounds of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chapter 7 of The City of Wonders, in which the children will get on a sidewalk that moves and a battleship that doesn’t.]

NOTES

[1] “I shot an arrow into the air” This Edison recording is of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem “The Arrow and the Song.” A parody from the Yale Record appeared in the April 7, 1904, issue of The Independent:

I shot an arrow into the air;

It fell to earth I know not where,

Till a neighbor came and raised a row

Because I shot his Jersey cow.

I breathed a song into the air;

It fell to earth I know not where,

Till Edison came and gave me laugh—

He had it in his phonograph!

[2] “Here is a still more remarkable invention—the kinetograph” This curious passage from The City of Wonder appears to be describing the kinetoscope, not kinetograph. Edison’s kinetograph was a camera device for recording motion pictures. Edison’s kinetoscope was a mechanical device for viewing motion pictures. Although slated to debut in Chicago and widely reported to have been on display at the 1893 World’s Fair, the kinetoscope was first unveiled for the pubic at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences on May 9, 1893. Chicago film industry historians Michael Glover Smith and Adam Selzer write in Flickering Empire: How Chicago Invented the U.S. Film Industry (Columbia University Press, 2015):“There are many references in works of historical non-fiction to the Kinetoscopes actually being present at the fair, including in Erik Larson’s The Devil in the White City, which describes the notorious serial-killer H.H. Holmes admiring movies on Edison’s machines. These references, however, are most likely based only on the advance publicity that insisted that the Kinetoscopes would be there.”

[3] “If one thousand boys and girls were each allowed one pound and two-thirds of seven-eighths of a pound a day, how many days would it take them to dispose of the 33,000 pounds?” 20.8 enjoyable days.