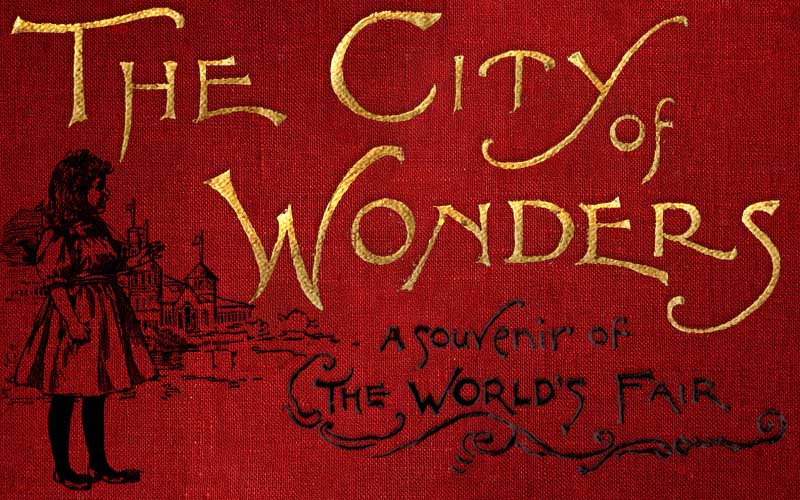

THE CITY OF WONDERS

A Souvenir of the World’s Fair.

BY

MARY CATHERINE CROWLEY

CHAPTER 4. MODES OF TRAVEL, OLD AND NEW

[For other installments of our serialization of The City of Wonders (1894), see the Table of Contents]

The Transportation Building of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, design by Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan. [Image from Graham, Charles S. The World’s Fair in Water Colors. Mast, Crowell & Kirkpatrick, 1893.]

“Since we have obtained an idea of the equipments of Columbus and the Vikings, suppose we go and see the exhibition of the modes of travelling nowadays?”

A ride on the Intramural Railroad brought them to the immense Transportation Building, which, in contrast to the marble whiteness of the others, was of a dull Egyptian red in color, and of Moorish architecture.

“Notice the splendor of this vast archway beneath which we enter,” said Uncle Jack. “Because of its beauty and richness it is called the Golden Door.”

Displays of ship models inside the Transportation Building. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“We can imagine we are just setting off for a tour around the world!” exclaimed Nora, as she tripped along gaily.

Vehicles of all types on display. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“Now we can trace the development of everything that goes upon wheels, from the first thought of this means of getting about to–what shall I say?” hesitated Mr. Barrett.

The display of a Chicago bicycle company in the Transportation Building. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“But this fac-simile of an old Roman chariot is so much more interesting,” declared Ellen.

“I am quite satisfied with these superb nineteenth-century equipages,” sighed Nora, lazily.

“See all these great engines and fine trains of cars!” said her brother. “One might imagine that the Grand Central Depot of New York was set down in this corner of the building.”

They inspected the Royal Blue Line Express of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad; the luxurious Pullman train, perfect in all its appointments; and the White Train of the English Exhibit, which was similar to that which runs between Liverpool and London.

“Oh, isn’t it pretty!” cried Nora, as they stood before the latter. “Do you not want to ride in one of those white carriages, Ellen? Here is one with the door open. How comfortable it looks! Like a coach, only larger, and with four seats on each side. Now I understand how people travel abroad, for Claire Colville wrote me that the same kind of railway carriages are used all over Europe, although they are usually painted a dark color.”

Uncle Jack and Aleck loitered to examine the locomotives, the different kinds of rails, etc., until the girls grew impatient. They were interested again, however, when they caught sight of the primitive engines, the queer, toy-like mechanisms from which the great Iron Horse of the present has sprung. Aleck, who had a taste for machinery, grew more enthusiastic and excited every minute.

“Some of these are reproductions, of the exact size of the originals.” began Uncle Jack; “but a number are the veritable engines.”

“Well, here’s old Samson!” exclaimed the boy, “No reproduction about that. I’m sure it looks as if it came out of the Ark. What a little thing it is, with its six small wheels, and the boiler encased in wood! What an odd smoke stack, too, just like a stove-pipe !”

“Come and see the Buffalo, built in Baltimore in 1844, and the first eight-wheeled locomotive in the world,” called Mr. Barrett.

“This funny one is the Camel,” said Nora. “And it is very well named, too; for does not the long narrow smoke-stack, with its slanted top, remind you of the head and neck of that awkward animal? And then it has such a droll, bell-shaped hump.”

“Ha ha!” laughed Aleck. “There is an engine with its cab on top of the boiler. Looks as if it were riding horseback.”

The De Witt Clinton locomotive on display in the Transportation Building. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“Don’t despise the fac-similes,” said Ellen. “Here is a quaint one of the Tom Thumb, which, the card attached to it says, was the first engine built, and the first to draw a train of cars, on the American Continent.”

“Ah!” rejoined Uncle Jack, “that must be the one constructed by Peter Cooper,–the same who, when he grew rich and famous, founded the Cooper Institute in New York, you know.”

Aleck, notwithstanding the sign “Hands off,” had been fidgeting about, patting and clapping every aged relic, as if it were a venerable war-horse. He bent over to read the inscription on the Tom Thumb, and announced that the first train was run on the 28th of August, 1830, from Baltimore to Ellicott City, a distance of thirteen miles, in an hour and twelve minutes.

“Just think, that was only sixty-three years ago!” continued Ellen. “And the engineer you stopped to speak to, said that some of those English locomotives back there can go sixty miles an hour–“

“Ho, another hoary veteran!” interrupted Aleck. “The Atlantic, built in 1832. It is marked as the first of the grasshopper class. Really, hasn’t it some resemblance to a gigantic grasshopper?”

“Would not you like to see it hop–go, I mean?” queried Nora.

They smilingly agreed that they would; and Aleck darted off to look at Old Ironsides, and several others with ludicrously lofty and slender smoke-stacks.

“What do you think of these for chimneys?” he asked. “Just notice that one at the end. It must be seven feet high.”

“It belongs to the Thomas Jefferson, the first engine to use anthracite coal,” replied his uncle.

French and Belgian locomotives on display. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“It is a fac-simile of the Cugnot, the first self-moving vehicle, or locomotive, of which there is record in history; and was constructed in 1769-71 by Nicolas Cugnot, an officer of the French army. His object was to find a means of dispensing with horses and mules for drawing artillery. Singularly enough, his invention has never been availed of or perfected for that purpose. The rudimentary idea of the inventors who turned their attention to the subject, was to make a passenger conveyance for use on common roads. Here, however, is the very first locomotive that ever ran on a railroad and drew cars. It comes from Cornwall, on the borders of Wales, the country of Jack the Giant Killer, you remember. No doubt, in the beginning, the story of this prodigy was regarded as about as worthy of belief as the exploits of that doughty hero. It is known as the Trevithick Engine, having been constructed by a Cornish miner of that name in 1804. Perfected, its speed was ten miles an hour. Near it we see a section of the peculiar strap railway on which it ran, and also two of the original cars.”

The girls and Aleck peered into them.

“What queer little things! It must have been like taking a jaunt in a bandbox in those days,” said Nora.

“They are more like the American than the English cars, judging from those we saw a while ago,” noted Aleck.

“Yes, that is a singular fact,” assented Uncle Jack. “But the origin of the latter is easily understood. The Englishman was accustomed to journey in his family carriage, or by the stage-coach. To render the new mode of travelling popular with him, it must be made as nearly like the old as possible; therefore, this carriage, or one resembling it, was simply transferred to the railway running gear. The same was the case also in other countries. In France, as late as 1853, one could have one’s travelling carriage thus attached to a train and continue to enjoy its comforts and seclusion during the journey.”

A display of the Great Western Railway of England. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

The young people stood laughing before it.

“Well! Well!” ejaculated Aleck. “The clumsy, lumbering old vehicles appear as if they had been suddenly aroused from a nap, and before they were fairly awake found themselves hurried along, at a break-neck speed, they do not yet know exactly where. They make me think of Rip Van Winkle.”

“Do you want to see a horse-legged locomotive?” asked Uncle Jack, who had wandered on.

Of course they did, and accordingly hastened after him to view a reproduction of the Brunton (English) Engine, which was built in 1803. They also made the acquaintance of Puffing Billy.

“Hello, old boy! “ cried Aleck, addressing this burly member of the locomotive tribe. “Why, you were a strapping big fellow for those days; and a great blower, too, I should judge by the size of the smoke-stack with which you are furnished.”

“Next,” said Uncle Jack, “we find fac-similes of the Blücher and the Rocket, the first engines of Stephenson, whose improvements on the earlier models were so great that his invention is considered the basis of the locomotive as we have it to-day.”

“I am sure this looks ancient enough,” Ellen remarked.

“Let us go back to our own country,” Aleck proposed, as if they had been roaming through distant lands.

Turning into another aisle, they discovered several of the early American engines which they had missed before. As they paused before a quaint steam-carriage of obsolete construction, Mr. Barrett said:

“We have seen the first engine which actually drew a train on our Continent. This represents the first recorded idea of steam propulsion in the Western Hemisphere. It was invented in 1790, by a man named Nathan Reed, of Salem, Massachusetts. This and the Tom Thumb are reproductions; but now we will go and see the oldest original locomotive in America.”

Uncle Jack led his party through many aisles and cross aisles, and amid a maze of railway tracks, engines and cars, until they reached one of the great gates of the building. Going out and crossing a courtyard, they came to the exhibit of the Pennsylvania Railroad, which showed a whole system of tracks and signals, a handsome station, etc. At one of the platforms, where it had drawn up when it steamed into the Exposition grounds, they beheld a very small, antiquated locomotive and train.

The John Bull engine on display in the Transportation Building. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“I suppose you will be comparing your elderly uncle to the John Bull presently,” complained Mr. Barrett, with mock seriousness. “But if so, then all of you must be the little cars which I have to drag along with me.”

The others laughed.

“Isn’t it an interesting old engine?” said Aleck, walking around it in delight. “This card says it went into service in 1831 and was first used on the Camden & Amboy Railroad. It was exhibited at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, and again at the Chicago Railroad Exposition in 1883. On the 17th of April of the present year it left New York city under steam, and without assistance hauled these cars, known as the John Bull train, the nine hundred and twelve miles to Chicago.”

“When you can tear yourself away from that intrepid old campaigner, my boy, we will come down a little nearer to our own times,” said “Mr. Barrett, after a while.

They retraced their steps across the court and came to another engine, before which Uncle Jack paused, saying:

“In its way, this is almost as interesting a memorial as any you have seen. It is the Pioneer, the first locomotive that ever ran out of Chicago, the metropolis which is now the starting point and terminus of more railroads than any other city of the United States.”

Still Uncle Jack led on, till the girls declared they were “ready to drop” from fatigue, and Nora suggested that they would have to be sent home in one of the ambulance trains exhibited by the Red Cross Society, and intended for use in war times. At last he brought the party to a halt before a magnificent-looking locomotive which an employee was occupied in burnishing.

“The man evidently takes as much pride in his work as the Arab does in rubbing down the glossy coat of his steed,” he observed. “Notice how admiringly he regards the Flyer,–much as the owner of ‘Boundless’ might gaze upon that plucky race-horse, which won the American Derby the other day.[1] And well he may, for this is the locomotive which has made the greatest run ever attempted in America.”

The Empire State Express engine No. 999 on display in the Transportation Building. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“Yes,” was the response. “The engine that recently drew the already famous fast train from New York to Chicago, and made during the trip the marvellous record of one hundred and twelve miles an hour.”[2]

They saw also the immense Baldwin Engine, the largest locomotive in the world. Uncle Jack informed them that it was built for the Mexican Central Railway and intended for drawing freight cars over the heavy grades between Tampico and the City of Mexico.

“The weight of this machine is 130 tons,” he said. “It has, you see, the appearance of two locomotives of the Mogul pattern backed up together, with the two cabs joined. The engineer sits on one side of the cab; on the other the fireman pours in fuel; while the services of a third man are required to pass up the coal.”

[This ends the Kendrick family’s first (long!) day at the 1893 World’s Fair. In Chapter 5 of The City of Wonders, the children will begin their day exploring exhibits from nations around the world inside the largest building in the world.]

NOTES

[1] “which won the American Derby the other day” Although the 1893 Kentucky Derby was held on May 10, other textual evidence suggests that this story is set in mid July.

[2] “Is it the celebrated 999?” Shortly after the record-breaking run of the Empire State Express engine No. 999 on May 10, 1893, it travelled to the World’s Fair in Chicago. Retired from service in 1952, the engine returned to the old fairgrounds in 1962 to become part of the collection of the Museum of Science and Industry, where it is on display today.