“Extremes meet at Chicago.” —librarian Caroline Harwood Garland.

The 1893 World’s Fair was full of contrasts: exotic dancing on the Midway and educational exhibits; fountains illuminated by electricity and bibles illuminated by paintings, dynamos and the Dewey decimal system; balloon rides and books. Amidst the Cracker Jack and orange cider was also “food for reflection in the existence of so many libraries.”

To celebrate National Library Week, let’s take a look at libraries at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.

The fairgrounds offered several book nooks for bibliophiles visiting the Fair, most of which are described by Caroline Harwood Garland in her article “Some of the Libraries at the Exposition” from the August 1893 issue of The Library Journal. The original article has been reformatted slightly with section headers added and with added footnotes.

Some of the Libraries at the Exposition.

By Caroline Harwood Garland, Dover (N. H.) Public Library.

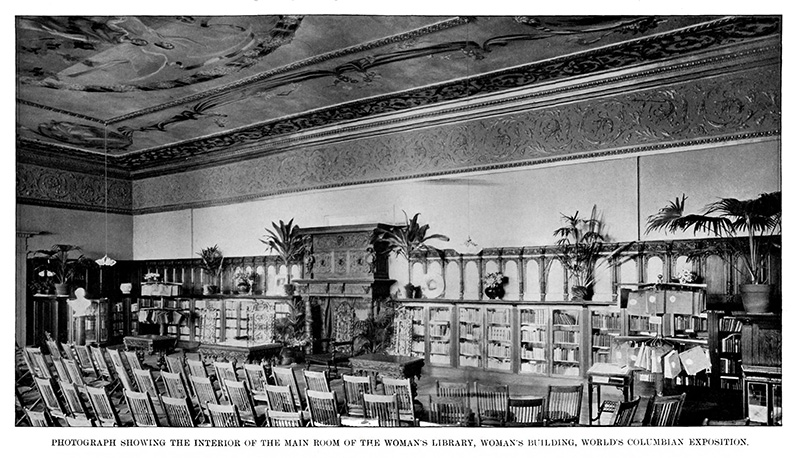

The Woman’s Building library. [Image from “Woman’s Library” Campbell, James B. Campbell’s Illustrated History of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Volume II. M. Juul & Co., 1894, p. 367.]

In this room shall be gathered the books of women

Perhaps the one most beautiful room in all the buildings at Jackson Park is the library of the Woman’s Building. It is the design that in this room shall be gathered the books of women written from all over the world. The room itself is the gift of the women of New York State. It is spacious, being 60 feet long, 40 wide, and 20 high, and beautiful, being decorated under the special supervision of Mrs. Candace Wheeler. The ceiling painting is by Dora Wheeler Keith. The wainscoting of old English oak is seventeenth century carving, from an old French cathedral. The chairs are of carved oak from Sypher’s [1] and decorated leather from the Associated Artists.[2] Screens, cabinets, busts, and portraits lend their aid to make the whole effect of great beauty and dignity.

The books, some 7000 in number, are arranged in low cases around the walls of the room. The captious critic may suggest that this is not in accordance with advanced library ideals, but it must be remembered that this is not a working library, but an exhibit, and as such should be arranged as artistically as possible. In point of number New York State largely leads, showing 2400 books; Pennsylvania comes next with 400; New Jersey has 350. The others range from 100 down, much depending on the zeal of the collecting committee. Massachusetts, which can count up more women writers probably than any other State, is here represented by less than 100 volumes, because the committee from that State decided that quantity was nothing, that quality was everything, and that nothing but the very best of its kind should be sent, and only one book from an author. The result is a small collection of picked volumes, and great ire on the part of many Massachusetts women.[3]

“This is the story of my life”

Many of the books have a curious interest attaching to them. “This is the story of my life,” remarked one old lady, who, attended by a sedate colored servant, brought her book in person. “This book has changed the legislation of 32 States.” At some length she explained that when she was a young woman her husband had shut her up in a mad-house in order to obtain possession of her property. After three years’ confinement she escaped, found friends, wrote her books, and then made successful applications to the States for better legislation in regard to the insane.

The number of rising young Western authors who visited the library was past enumeration. They were as a rule hopeful and entirely free from the vice of modesty. “You’ll read it, won’t you?” demanded one of them, as she put her book into the librarian’s hand. “If I have time,” was the cautious reply. The author seized it back again. “I won’t leave it if you don’t promise to read it!” Thereupon the librarian’s desire to increase the size of the library got the better of her truthfulness.

A color plate from Genevieve Estelle Jones’ The Nests and Eggs of Birds of Ohio. [Image from Smithsonian Institution Libraries, Washington, D.C.]

One most remarkable scientific work

With some of the books “In memoriam” is written between the lines. The one most remarkable scientific work comes from the State of Ohio. It consists of two large volumes, the price of which is $375. It is entitled The Nests and Eggs of Birds of Ohio. The preparation of text and plates cost the author, Mrs. N. E. Jones, eight years of untiring industry. “How did you ever have the patience to complete it?” asked the librarian. “I did it in memory of my daughter,” was the reply. “She had just begun the work when she died. So for her sake I made it as perfect as possible.”[4]

Foreign women have made contributions of great value. France sent about 800 volumes, many of them in beautiful bindings. Bohemia sent 300, Sweden 130, Italy 150, Germany 300, Great Britain 500. Word has been received that the women of Japan are sending 50, but they have not yet arrived.

The A.L.A.’s Model Library in U.S. Government Building. [Image from Johnson, Rossiter A History of the World’s Columbian Exposition Volume 3 – Exhibits. D. Appleton and Co., 1897.]

Model Library Mecca

The Mecca toward which the footsteps of all good librarians tend as soon as they land in Chicago is undoubtedly the library of the A. L. A. [5] over in the Government Building, familarly [sic] known as the Model Library. A gentleman and his wife interested in library matters asked a roller-chair guide who was bending over his chair, “Where is the Model Library?” “At Harvard College, madam,” replied the guide, without raising his head or giving an instant’s hesitation. It will be remembered that these guides are college men. It chanced that the inquirers were from Cambridge, and they were vastly pleased with the reply. The Model Library has been so well described in Miss Sharp’s paper that nothing need be added here.[6]

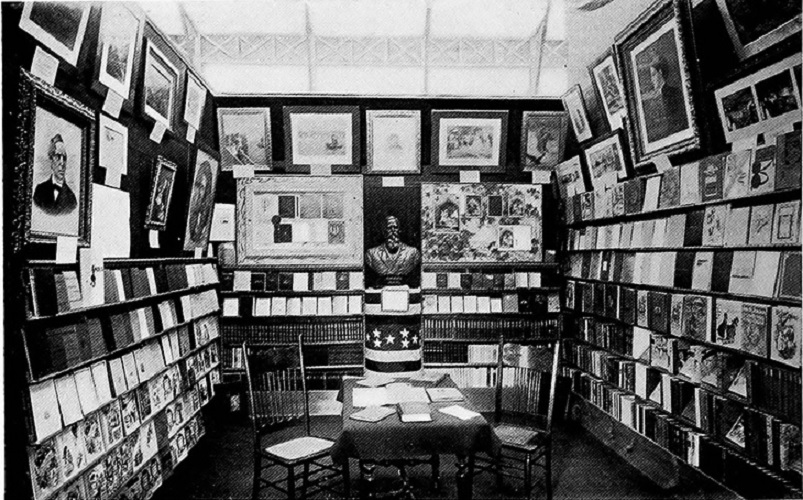

Photograph of the library of the Children’s Building. [Image from Jenks, Tudor The Century World’s Fair Book for Boys and Girls. The Century Co. 1893.]

Thronged with visitors all the time

In the Children’s Building is a well-selected young people’s library, of which Mrs. Clara Doty Bates has charge. The room itself is very attractive — being light, airy, and dimity-curtained — and is thronged with visitors all the time, not all of whom are children. The walls are decorated with portraits and photographs of writers for children, 60 faces being counted on one single wall. In a show-case in the middle of the room the Youth’s Companion make an interesting exhibit of the growth of their paper, showing a little old volume of 1827 alongside the present size. They also show interesting original manuscripts and cuts representing the growth of illustrations. In this room may always be seen children contentedly reading; sedate men and women making lists of books for the children at home; eager young faces studying the pictures on the walls; and the flying tourist, who puts his head inside the door, takes one glance and departs, thinking he has seen it all.

Collective display of objects and books in the main hall of the German Building. [Image from Unsere Weltausstellung. Eine Beschreibung der Columbischen Weltausstellung in Chicago, 1893. Fred. Klein Co. 1894.]

Extremes meet at Chicago

In the foreign buildings are to be found some very interesting collections of books. Those librarians who visited the German Building greatly enjoyed the displays there. Through the courtesy of the German commissioners the building was closed to the public one afternoon and the librarians were invited to inspect at their leisure these German exhibits. More than 300 firms are here represented. Large finely illustrated books lie open on the counters. Long lines of uniform sets are displayed, the Tauchnitz Library alone now numbering 3880 volumes. Perhaps the most interesting are the old ecclesiastical works, especially the fine old leather-bound, silver-mounted volumes, 3 feet long and 2 feet wide, filled with quaintly illuminated music. These books are still used by monks in some of the older monasteries. Not far from these — extremes meet at Chicago — is a fashion magazine, with editions published in 13 languages. And even if you pass all these quickly, you will be sure to linger over the educational books and the wide open atlases which, the attendant proudly assures you, show much finer work than anything that can be done in America.

The Swedish Building. [Image from The University of Michigan Library Digital Collections.]

Reception Hall in the Turkish Pavilion. [Image from Unsere Weltausstellung. Eine Beschreibung der Columbischen Weltausstellung in Chicago, 1893. Fred. Klein Co. 1894.]

Woven by hand in silk

If you dare venture past the hideous painted bull-fight that greets you as you enter Venezuela, you will find they have no books now, but a library is on its way. In Turkey are two book-cases standing honorably in the centre of the room. The Turkish attendant courteously explains that the 40 or 50 books contained therein are not specimens of their literature, but are government and educational books, exhibited for their exquisite bindings. There is also some music in the case worthy attention. It bears the name of Paderewski[7] and the imprint of Constantinople. You notice that the notes are wonderfully fine and clear, but not till you examine it closely do you see that these intricate bars of music are not printed at all, but are finely woven by hand in silk on delicate white gauze.

Costa Rica, in its gay little building, has a whole case devoted to national and school books. Each book is opened at its title-page and braced stoutly from behind up against the glass, challenging at least a passing glance. Guatemala displays 25 or 30 books, bordering them with bottles of wine on one side and tobacco on the other. One is opened at its title page, which reads, A Book of the Arts of Guatemala, 1793. But this little historic thing is quite overshadowed by a pretentions album, lying open at a picture of the crescent moon hanging before a balcony from which a woman, presumably lovely, leans. Guatemalan fiction is thus evidently en rapport with that of other lands.

Brazil has no library and displays only a few albums of native scenery. East India has a bazaar but no books. Ceylon has quite a collection of books, neatly cased, chief among them being a Singalese grammar, a work on Domestic Economy, a sanitary primer — its pleasing title being Sukhopadesaya — a Book of Common Prayer, and the Ceylon Blue-Book for 1891. From these last two items it will be seen that Ceylon is provided with the actually necessary literature for the establishment of good society. Down in the Javanese village [8] they have no library, but literature is not entirely neglected, for they prominently display the sign, “Albrecht & Rusche, General Printers of Poetical and Prose Works in the Polynesian Languages,” and directly in front of the sign sits a gray-haired man threading his needle, for Java is an advanced country and the men do the sewing.

An inside view of Victoria House. [Image from Unsere Weltausstellung. Eine Beschreibung der Columbischen Weltausstellung in Chicago, 1893. Fred. Klein Co. 1894.]

The whole elegant library is a complete sham

By far the most imposing library on the grounds is that in the Victoria House. The room itself is a model English library, being finished entirely in oak, the ribbed ceiling in geometric form, the sides in panelling; soft, thick rugs are on the floor; the arm-chairs are modelled from originals in the Cluny and South Kensington museums. Around the walls are the leather-decorated book-cases, filled with elegant bindings. The librarian accustomed to the tattered books of a public library stands awe-struck at the beauty of the full sea of English poets and novellas, art journals, and quarterly reviews in elegant calf and morocco. One watches a chance when the attendant is not looking and inserts an adventurous finger to pull out a book, thinking to see if the letter-press equals the binding. The book does not come out, but the finger does. The book is not a book at all, but a dummy binding tacked on a strip of wood. The whole elegant library is a complete sham.

Lithograph of the Indiana State Building. [Image from Vistas of the Fair in Color. A Portfolio of Familiar Views of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Poole Bros., 1894.]

The general art of “getting there.”

Many of the State buildings have good collections of their State literature, the Western States showing especial zeal in this direction. Indeed these Western States show an enterprise quite appalling to a steady-going Easterner, not only in the book line, but in the general art of “getting there.” A call at the Indiana State Building may be cited in evidence. They have a fine reading-room here, with tiled floor, ample chairs, and great clear windows. About 300 Indiana papers are kept on file and two book-cases display 600 books by Indiana authors, Lew Wallace, James Whitcomb Riley, and Sarah K. Bolton being their best-known names. As the librarian made a note or two, the competent Indiana woman in charge of the room asked:

“What paper do you write for?”

The librarian modestly replied that the Library Journal had thought it might like an article about the different libraries at the fair.

“What is the Library Journal?”

The librarian, seeing a chance for missionary work, gladly explained.

“I’m glad to hear about that paper,” replied the Indianian. “We ought to have it here in the library, oughtn’t we ? What is their address?”

Great hopefulness on the part of the librarian that a new subscriber had been gained for the L. J. The Indianian continued:

“I’ll write them right off to-day and ask them to donate their journal to the library here. No doubt they’ll be glad to do so.” Silent departure of the librarian.

In the Illinois State Building there is a good little collection of books by the women authors of the State, Mary Hartwell Catherwood, Clara Louise Burnham, and Margaret Bouvet being the best-known names. There are perhaps 500 books in all, and this is a record to be proud of when one remembers that the first woman’s book in the State was published in 1854. The title of this first book was Early Engagements.[9]

The Reading Room in the Wisconsin State Building. [Image from Unsere Weltausstellung. Eine Beschreibung der Columbischen Weltausstellung in Chicago, 1893. Fred. Klein Co. 1894.]

Well versed in the ways of the craft

Whoever arranged the library in the Wisconsin State Building was well versed in the ways of the craft. There are about 500 volumes, well classified and clearly labelled. Local history is very well represented. In fiction the leading names are Björnson and Captain King; in history, R. G. Thwaites; while in poetry Ella Wheeler Wilcox shines. The room itself is inviting, being large, low-storied, with divans, low, comfortable chairs, and pleasing effect of warm light wall tints. Framed on the wall hangs the original ms. of The Sweet Bye and Bye, sold by its author for $1000.[10]

Nebraska has a reading-room with a large cuspidor for its central ornament. The State of Washington, as it loves to label itself, has a small reading-room and large rocking-chairs, but no books. California has a small library — Bret Harte and H. H. Bancroft [11] being prominent names — enclosed in a curious burnt-wood pavilion in the centre of its great building.

In the library of Utah Mormon books predominate. In Idaho’s Building — a unique building, representing a miner’s cabin — on a cedar shelf overhanging the great fireplace of lava-rock, are ranged some 20 or 30 books, Mary Hallock Foote being given the place of honor. “We got all we had,” frankly confessed the woman in charge. “But we’re young yet. We’ve got good material and we’re going right ahead. ‘Twon’t be long before we make Massachusetts hustle to keep up with us.”[12]

South Dakota shows beautiful petrified wood, but no books. North Dakota smells of grain, and the search for a library led one up-stairs where reception-rooms had been furnished by different towns. The room labelled Devil’s Lake was evidently a reading-room, for here, in well-tipped chairs, sat two men, their legs crossed over the table. The soles of their boots and two wide-spread newspapers were the most conspicuous contents of the room.

The Kansas State Building interior. [Image from Campbell, James B. Campbell’s Illustrated History of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Volume II. M. Juul & Co., 1894, p. 379.]

Cheery reading-rooms

Iowa’s library is characteristic of her building, being large, generous, not over-orderly, but easy of access. It is in a pleasant, airy room, with windows open to the lake breezes, and all are welcome to walk up to the shelves and help themselves. In consequence of this liberty the books were not arranged in strict D. C. The Destiny of the Wicked stood calmly between a W. C. T. U. report and a State document. Files of agricultural and school reports, however, were in irreproachable order. There is not much fiction in the library, but Octave Thanet and Hamlin Garland [13] are well represented.

Kansas has a large building and a good deal in it. Its library is in a great room up-stairs, and consists of books not only by Kansas authors, but on Kansas subjects. Its slavery struggles, its early tragedies, its prosperous career — all are described in its literature.

Warm yellow and pink tones please your eye as you enter Arkansas, and you are greeted by an abundance of literature concerning the State itself. Home-seekers are warmly invited to appropriate the pamphlets and circulars. Up-stairs there is a cheery reading-room with the State newspapers, and an entirely unique library, composed of handsome wooden dummies, each dummy representing some special wood and labelled where the title of the book should be with the name, scientific and common, of its material.

The Kentucky State Building. [Image from “Kentucky at the Exposition” Campbell, James B. Campbell’s Illustrated History of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Volume II. M. Juul & Co., 1894, p. 371.]

You feel that life is not a failure

Colorado, Texas, and Louisiana have no libraries. Kentucky has a very pretty book-case, in which Mrs. Holmes figures largely.[14] Maryland has a collection of the very valuable publications of the Johns Hopkins University. New Mexico, Arizona, and Oklahoma, all under one roof, have no libraries, but support reading-rooms, well stocked with papers. Florida has no books nor papers, but they serve you orange cider, and you feel that life is not a failure. Ohio, or “Ohier,” as the natives have it, has no books, but in its reading-room every chair was occupied by a newspaper reader.

Missouri’s library is like many other things at Chicago. She hasn’t it now, but is going to have it. The hostess of the room assured the librarian that their library was “going to be” one of the best State libraries on the grounds; to all of which the librarian listened politely, but silently, until the Missourian said the selection and collection had been made by Mr. Crunden, of St. Louis. Whereupon the librarian made haste to add her own assurance that such being the case it certainly would be everything that was right.[15]

The Maine State Building. [Image from “Maine State Building” Campbell, James B. Campbell’s Illustrated History of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Volume II. M. Juul & Co., 1894, p. 426.]

Some hot secession literature

You have to hunt a little to find the Pennsylvania books, for the building is large, and the book-case small and mostly filled with decorated china. New York exhausted itself on the fine collection for the library of the Woman’s Building, and has no collection of books in its State Building. Virginia’s building, which is a reproduction of the Mount Vernon mansion, has a very interesting library. It is rich in old Virginia material, containing some hot secession literature, now standing peacefully on the shelf by the side of the work of the new South.

Of the New England States Maine is the only one that has a library,[16] and Maine has a very good one. Portraits of authors adorn the walls and the books are of wide range and noteworthy of their kind, Blaine’s book and Sarah Orne Jewett being good examples.

An exhibit in the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building from D. Lothrop & Company publishers of Boston. [Image from Johnson, Rossiter A History of the World’s Columbian Exposition Volume 3 – Exhibits. D. Appleton and Co., 1897.]

A great library worthy many days’ study

It would be difficult to enumerate the libraries in the large buildings. Nothing can show more clearly the part that books play in the practical work of life than these little technical collections, displayed everywhere as part of the working material of the exhibit. In the Mining Building, for example, in the Russian department are 125 uniformly bound books on mining; in New South Wales, 25 large folio reports; in Canada, reports in French and English of the geological commission; in Spain, a long shelf of Mapa Geologico; while in the Liberal Arts Building, the publishers’ section, already described in these columns, forms a great library worthy many days’ study. The miscellaneous libraries are quite “too numerous to mention.” For examples may be cited the Bible Society’s collection, containing 800 Bibles, no two alike ; the library on the Brick Battleship Illinois, of seamanship and American history ; the books on trade-marks, in the English, Spanish, German, and Swedish languages; and down in Music Hall, Theodore Thomas‘ great musical library, at present the bone of contention between his friends and the Fair authorities as to whether the large sum demanded for its rental shall be paid.

There is food for reflection in the existence of so many libraries. The unprejudiced librarian must wonder whether it is not well, in order to make a success of one’s self, occasionally to give over cataloging and classifying for others and read a little for one’s own benefit.

A map of book exhibits on the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition fairgrounds. [Image from Library Journal, July 1893.]

NOTES

[1] Sypher & Company was a New York antiques dealer.

[2] The interior designer collective Associated Artists formed in 1879 as a collaboration between artist Louis C. Tiffany & Company, painter Samuel Colman, the painter and furniture designer Lockwood de Forest, and the textile designer Candace Wheeler, who in 1883 led the firm.

[3] For more about the Woman’s Building library, see Wadsworth, Sarah; Wiegand, Wayne A. Right Here I See My Own Books: The Woman’s Building Library at the World’s Columbian Exposition. Univ of Massachusetts Press, 2012.

[4] Inspired by John James Audubon’s magnificent engravings for The Birds of America, which she was while visited the 1876 Centennial World’s Fair in Philadelphia, Genevieve Estelle Jones created her own illustrations of additional nests and eggs. She began her beautiful and informative volume in 1877, but died from typhoid fever in 1879. Her family completed Illustrations of the Nests and Eggs of Birds of Ohio, with text by Howard Jones, and published it in two volume 1879 and 1886.

[5] The A. L. A. is the American Library Association.

[6] Sharp, Katherine L. “The A.L.A. Library Exhibit at the World’s Fair” Library Journal Aug. 1893, 280-84.

[7] Garland presumably means the Polish pianist Ignace Paderewski, himself a notable presence at the World’s Fair that summer when he was a central figure in the great “piano war” that arose at the Columbian Exposition’s inaugural concert on May 2, 1893.

[8] In her tour of Fair libraries, Miss Garland has jumped from the section of foreign buildings in the northeast part of the main fairgrounds over to the Midway Plaisance. It is worth remembering that the Java Village, like other international villages on the Midway, were private concessions and not official displays by foreign governments.

[9] Early Engagements (1854) by Sarah Marshall Hayden was the first novel by an Illinois woman, though published by the Cincinnati firm of Moore, Anderson, Wilstach & Keys.

[10] Sanford Fillmore Bennett wrote the hymn “In the Sweet By-and-By” in Elkhorn, Wisconsin.

[11] Hubert Howe Bancroft’s name became inseparable from the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition due to his notable history, The Book of the Fair (The Bancroft Company, 1893).

[12] Idaho had joined the Union only three years earlier, on July 3, 1890.

[13] Hamlin Garland was quite impressed by the Fair, and famously writing to his father: “Sell the cookstove if necessary and come. You must see this Fair.” (Garland, Hamlin A Son of the Middle Border. Macmillan, 1917.)

[14] Mary Jane Holmes (1825–1907) wrote her first novel, Tempest and Sunshine, in 1854.

[15] Frederick Morgan Crunden (1847–1911) was head librarian of the St. Louis Public Library and the recent past President of the American Library Association (1889–1890).

[16] In her near dismissal of the contributions of her home region of New England, Garland missed the library in the Massachusetts Building. Massachusetts was proud enough of their commonwealth’s libraries that they displayed a map of “Free Public Libraries of Massachusetts.”