“Cephalopod Week” on NPR’s Science Friday celebrates the “amazing, adaptive, and sometimes creepy” family of sea creatures that includes the squid, octopus, cuttlefish and nautilus. Among the wonders of the 1893 Word’s Fair lurked several tentacled delights.

Armed with sucking disks on its tentacles

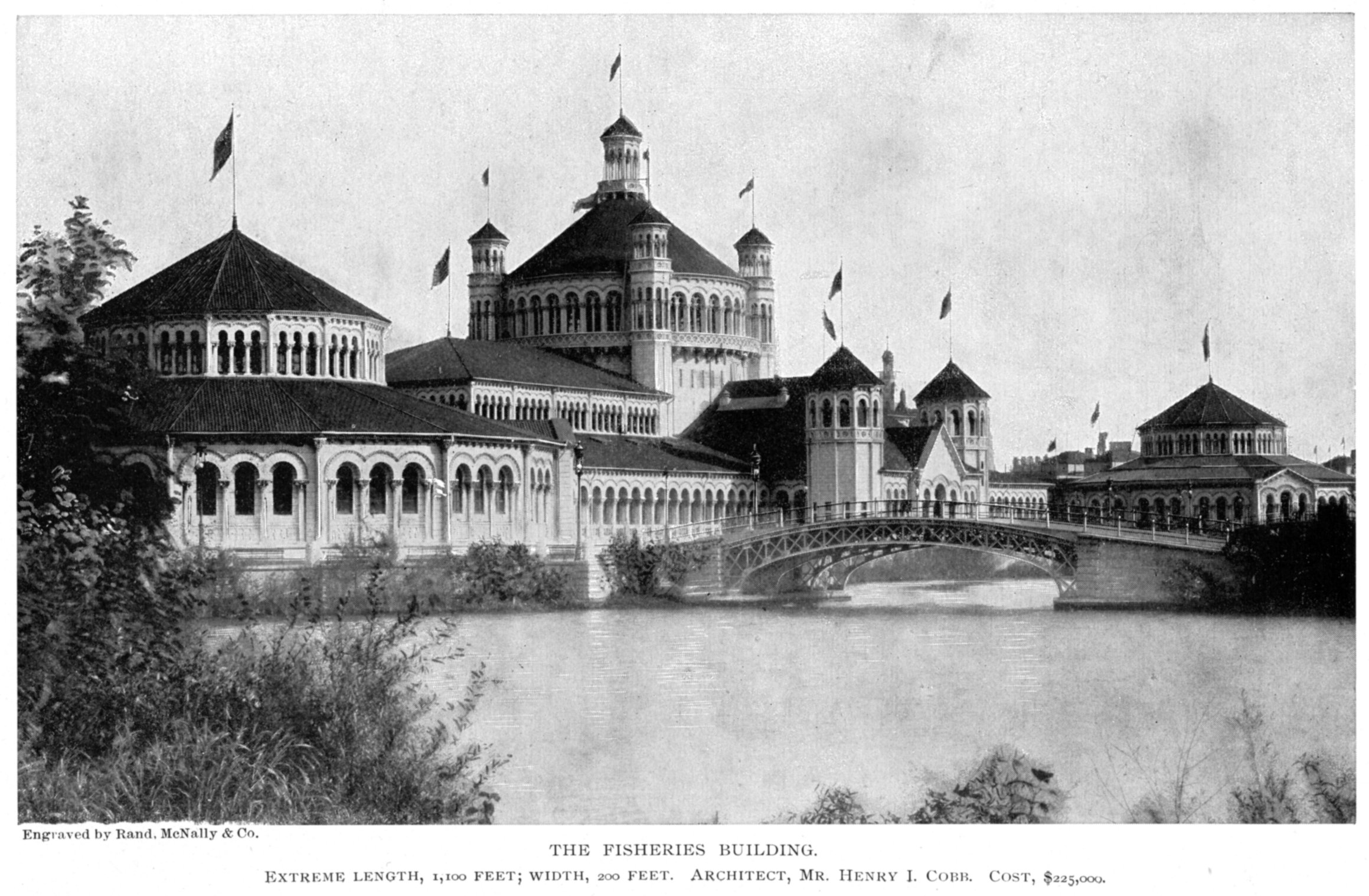

Visitors to the 1893 World’s Fair could view cephalopods inside Henry Ives Cobb’s beautiful Fisheries Building. Trumball White and William Igleheart’s World’s Columbian Exposition Chicago 1893 (P. W. Ziegler, 1893) describes some of the attractions inside Fisheries:

The inhabitants of two-thirds of the earth’s surface, as well as of the air, are here in almost endless profusion and variety, demonstrating in the most emphatic manner the scientific skill, energy and devotion that have been necessary to bring together these collections. The resources of art, of taxidermy; the naturalist’s skill and modern methods of refrigeration, have been fully drawn upon. The wonders of aquatic life, in all their glorious brilliancy of color and marvelous variation of form, are reproduced in paintings, colored lifelike casts of plaster and gelatine, in mounted specimens, in alcohol, in translucent blocks of ice and beneath the glass fronts of refrigerators. The mind is bewildered. Fish of all the earth, corals, sponges, algae; mollusca of all kinds, including oysters, clams and many other forms of shells ; squids of various sorts and the great octopus—the devilfish of British Columbia—armed with sucking disks on its tentacles; star fishes, sea urchins, holothurians, lobsters, crabs, cray fish, shrimps and other kinds of Crustacea; reptiles, such as turtles, terrapins, frogs and alligators; aquatic mammalia—whales, porpoises, seals, sea lions, white bears, otters and beavers—jostle and crowd each other at every turn. The baby cod or trout, newly hatched, stands in strong contrast to the 82-pound salmon from the Columbia river (sent here by Oregon in a solid block of ice), or the monster sharks or sword fish of the Atlantic.

Hubert Howe Bancroft’s The Book of the Fair (The Bancroft Company, 1893) mentions “well preserved specimens” of squid being on display in the Washington section (p. 524) and Canadian section (p. 532) of Fisheries.

The Fisheries Building [Image from Elliott, Maud Howe Art and Handicraft in the Woman’s Building of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 (Goupil & Co., 1893).]

Its hideous tentacles reaching out

Another teuthological wonder, on display in the Anthropological Building, was a giant octopus spanning 18 feet overhead. Bancroft describes the fascinating exhibit (p. 651):

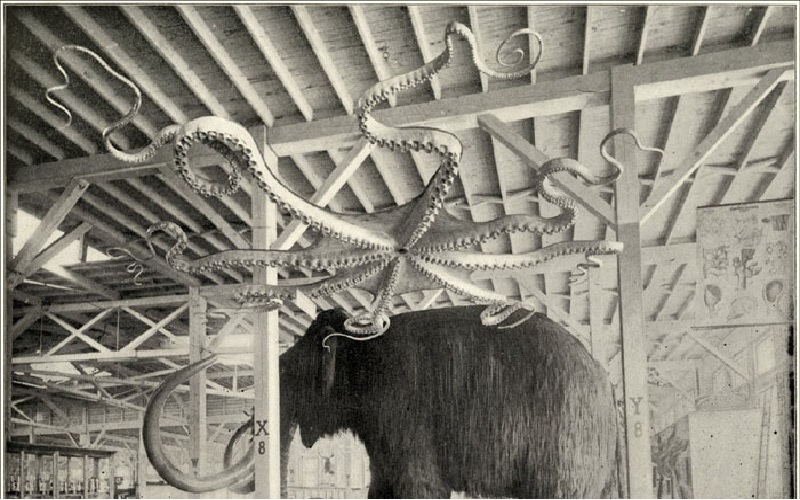

Occupying the entire southern aisle is the collection from Ward’s Natural Science establishment, of Rochester, New York, in the centre of which is the Siberian mastodon, reproduced from the royal museum at Stuttgart, 16 feet high and with curved tusks six feet in length. Among the remains of mastodons taken from the ice near the mouth of the river Lena, during the eighteenth century, were portions of skin covered with long, coarse hair. Thus, with the skeleton reconstructed, scientists were enabled to clothe it as here represented in its natural state. Near by is the huge frame of a plesiosaurus, 22 feet long, the original of which was unearthed from English soil. The ichthyosaurus, the megatherium, the gigantic elk of Ireland, the wingless moa from New Zealand, the armadillo from Montevideo, and other evolutionary forms of bird, beast, and fish are also displayed in skeleton form or as casts, many of the latter taken from the British museum. Suspended from the gallery ceiling is the skeleton of a whale, and elsewhere a huge octopus with arms outstretched as if to seize its prey. Other specimens there are, from those of mammals, especially deer, elk, and moose, largely from Maine and Colorado, down to trilobytes, corals, and crustacea, together illustrating the progressive forms of animal life through many geologic eras.

A giant octopus model and a woolly mammoth on display in the Anthropological Building of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. [Image from Photographs of the World’s Fair (Werner Co., 1893).]

… this giant papier-mâché octopus appeared in the Anthropological Building of the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. The man who made the model—James Henry Emerton, an arachnologist and scientific illustrator—never saw a live specimen of this animal, a giant octopus from the Pacific Ocean off California (Enteroctopus dofleini). Emerton had to rely on studying specimens preserved in alcohol; he used measurements of an octopus reported in a scientific paper as the guide for its size. And he made it life sized! The arms on the model span 18 feet in diameter.

Giant octopus model on display at the Field Museum’s 2013 exhibit “Opening the Vaults: Wonders of the 1893 World’s Fair” [Image from the Field Museum.]

To imagine what fair-goers in 1893 may have thought, consider this description of the exhibit from Photographs of the World’s Fair (Werner Co., 1893), written with typical Victorian-era romance and hyperbole. (Note: the display was of a mammoth, not a mastodon.)

MASTODON AND DEVIL FISH. Much has been said concerning the Exposition as an educational institution. It’s effects in this direction can not be overestimated. The scope is so broad and far-reaching that its benefits to the human mind will become, as the years roll by, more and more apparent. There is no field in which its influence has not been felt, no region of thought, learning or enterprise that has not received a wonderful impetus from the great event. Art in all its branches has already felt and will continue to feel the stimulus; science has gained a wonderful momentum; mechanics will be benefitted and as it advances mankind will reap its share; literature has been stamped with the mark of progress and the spread of knowledge will be without limit. In no department have the opportunities for study been more freely offered than in anthropology. The exhibit in this department and that of ethnology is as complete as is possible for man to make it. The selection above gives but a meager idea of the whole extent of the display. Here is seen only a mastodon, one of that extinct species of elephant scientists tell about, and clinging to the ceiling with its hideous tentacles reaching out as if in search of prey, is an octopus. a marine creature of the mollusca, which is sometimes called the devil fish. The building from one end to the other is filled with objects every bit as interesting as the above, and all supplying an admirable field of study.